https://twitter.com/DonnaLanclos/status/1012648911004225536

I have been lucky and been invited to give two talks this week, and I’m blogging the second one first, in part because it’s mostly text and no images this time around. Leo Appleton invited me to be one of the speakers at Goldsmith’s library staff development day, where the theme was “What does diversity mean for Goldsmiths and how can Library Services contribute?”

As usual, this is an imperfect representation of what I said in the room.

************************************************

“Maybe We Shouldn’t Talk About Diversity Anymore”

I want to thank Leo for asking me to talk to you all. I’m afraid this isn’t gonna be a fun talk. I’d apologize, but I think really it’s not a fun time, and we’re all tired, and it’s useful sometimes to acknowledge that things are hard, and that there’s more hard work to do.

This is one of those times.

This title is cranky, and it’s cranky in part because I’m generally upset with the state of the world, which is not quite literally on fire, but it’s damn close.

We are in a political moment where no one is safe, but those who have not been safe for a long time–the poor, people of color, LGBT+ folks, in many ways anyone who is not a reasonably well off white man–are feeling it the worst.

My country is putting asylum seekers in prison. Children in cages (but now, along with their families, too). We will be losing another Supreme Court Justice (the previous one was stolen) and we face the loss of voting rights, abortion rights, civil rights, and much more. Lies and propaganda fly out of the mouthpieces of our political “leaders” and those who seek to bring truth to power are accused of “incivility” when they are not ignored, or told that things would have been just as bad with the “other side” in power.

I’m not here to give a talk about politics, but it’s impossible to avoid because it suffuses every aspect of how we have to live our lives. And that includes in libraries, public and academic. And it has implications for what we talk about when we talk about “diversity.”

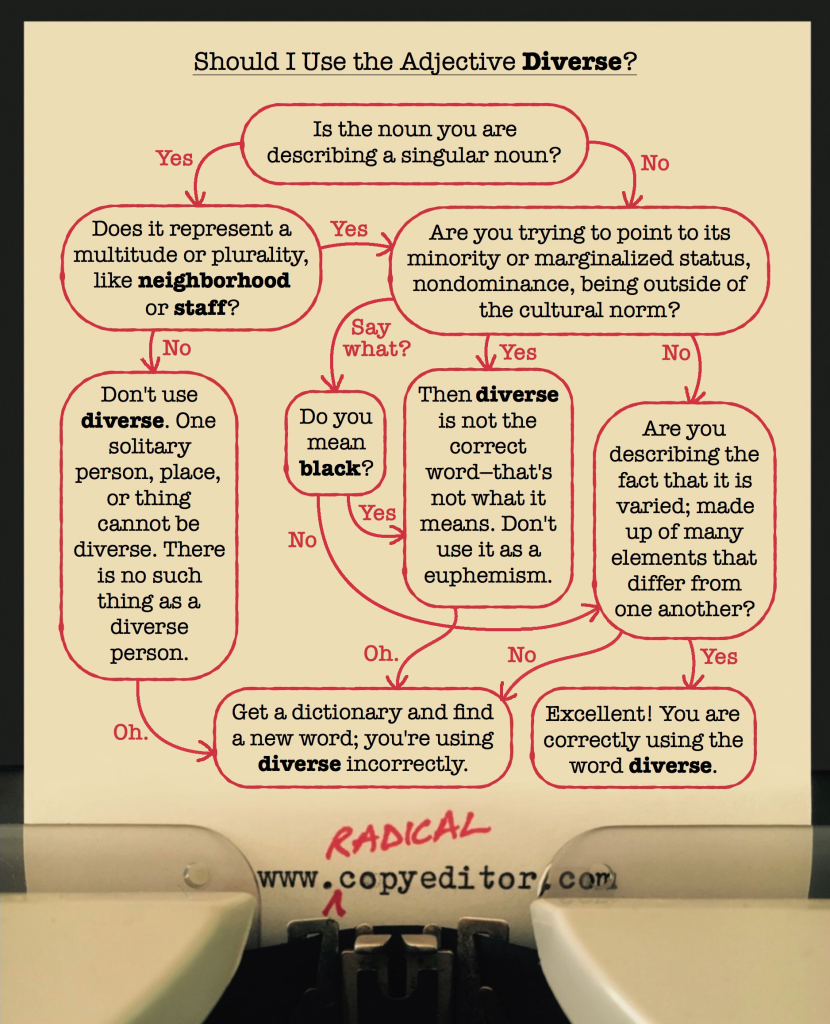

There’s a lot of talk about “diversity” in library staff these days, which is why I find this flow chart so important and so useful.

Far too often “diverse” and “diversity” are the words used when actually we should be talking about “difference” or “race” or “gender.” It becomes a euphemism, a signal that people don’t want to have difficult conversations, that they are comfortable, and they are signaling in their willingness to talk about “diversity” their unwillingness to actually talk about what needs to be done to create an environment where a wide range of people are not just comfortable in organizations but have access to power.

So I think it would be better for us to be concerned about the unrelenting whiteness of libraries, and the ways that the composition of the library profession reproduces race, gender, and other power inequalities that exist in our society.

I was inspired to see this sentiment coming out of part of the ALA tweetstream not long ago. These tweets particularly caught me, from the panel on Topographies of Whiteness, in the context of preparing these remarks.

(see Kristyn Caragher’s work with Anti-Oppression workshops for more on this)

How can we be inclusive if our very structures oppress the people who might work in these spaces, who occupy them as students, if these spaces were not really built for them? If the ways they can “belong” are to change themselves, rather than for these spaces and institutions to change. Think about how many times you’ve heard the term “professional”–what does that mean? Who does it leave out?

We should think about the role of gatekeeping in libraries. What role has credentialism played in the landscape of academic libraries that we see now? What role have assumptions about who is a part of libraries, and who, in particular, is the keeper of “proper” library behaviors, played in keeping people out of the profession, or driving them away when they do try? Or even the divisions within libraries, between “librarian” and other people who work in libraries–why are they not all called library workers? Why is the MLIS weaponized against people who have their own expertise within libraries?

I have worked in libraries since 2009. I do not have library worker credentials. And yet, I am qualified. I have also been told too many times that the work I do outside of the building is not relevant to the work inside the building.

How many of you have heard that? Been told that? Said that to someone else? How may have heard or said “that’s not in your job description?”

I want to point here to the work of these three women, Fobazi Ettarh, April Hathcock, and Chris Bourg. Since I have been working in libraries, they have formed part of my lodestone, my guiding principles in library work, and really my work in academia generally. If you haven’t read their work, or followed them on social media, you should, because they are doing important work that deserves wide attention. I don’t want to appropriate their voices, I want to boost them, point to them, listen to them.

From Fobazi Ettarh’s article “Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies we Tell Ourselves,” I want to highlight two quotes in particular. First, her definition of “vocational awe”

“Vocational awe” refers to the set of ideas, values, and assumptions librarians have about themselves and the profession that result in beliefs that libraries as institutions are inherently good and sacred, and therefore beyond critique.

She lays out the implications of a “professionalism” that valorizes self-sacrifice and the homogenization of self to a white, middle-class, physically able, “comfortable” norm.

But creating professional norms around self-sacrifice and underpay self-selects those who can become librarians. If the expectation built into entry-level library jobs includes experience, often voluntary, in a library, then there are class barriers built into the profession. Those who are unable to work for free due to financial instability are then forced to either take out loans to cover expenses accrued or switch careers entirely. Librarians with a lot of family responsibilities are unable to work long nights and weekends. Librarians with disabilities are unable to make librarianship a whole-self career.

April Hathcock, in her article “White Librarianship in Blackface: Diversity Initiatives in LIS” makes it clear that “diversity” as a euphemism does not break down the problems of whiteness in librarianship, and in fact gets wielded to reify and further reinforce white norms in the profession.

Our diversity programs do not work because they are themselves coded to promote whiteness as the norm in the profession and unduly burden those individuals they are most intended to help.

She further makes the point that “diversity initiatives” that require people to conform to whiteness don’t actually result in diverse workplaces.

When we recruit for whiteness, we will get whiteness; but when we recruit for diversity, we will truly achieve diversity.

In her Feral Librarian blog, Chris Bourg gave us the text for her talk “For the love of baby unicorns: My Code4Lib 2018 Keynote” (for which she later caught a tremendous amount of shit from her fellow librarians, which I think is shameful).

She points to the tech leavers study that came out in 2017, and notes

…as much as we want to throw our hands up and claim diversity is a pipeline problem, the retention data tells us that we have problems with toxic work cultures and unfair practices driving women and/or people of color and/or LGBTQ folks out of tech as well.

Some additional reading around the topic of libraries and the problems that people have staying in them, or getting into them can be found with the work of Kaetrena Davis Kendrick, whose article “The Low Morale Experience of Academic Librarians” is terrifically important (and who is now doing a follow-on project with racial and ethnic minority academic librarians. )

In David James Hudson’s “On Diversity as Anti-Racism in Library and Information Studies: A Critique” there’s a wealth of good background for this entire discussion. And he makes the point, as do the others I cite here, that this is fundamentally a structural problem. This is not about individuals, or their good intentions, not about “meaning well” or “being nice.”

The tech leavers report that Chris cited surely has a companion piece yet to be written about library leavers. This is not just about who doesn’t come to the library,but also about who came, and then had to leave. What role did credentialism play? What about presentist policies where if people are not visible in the building, it’s assumed they are not doing the work of the library? (ridiculous, in these times of digital places and affordances). What about notions of “neutrality” and “nice” that talk about the importance of “all voices” when we really should be protecting voices that historically have no platform. Let’s end false equivalencies, and recognize that people who have traditionally had power and influence (especially white men) don’t ever really lose their opportunity to participate just because we make sure that people and especially women of color get to take up space and have their say.

We cannot continue to ask the people who are directly victimized by whiteness, heteronormative assumptions, and ableism to do this work on their own behalf. White people need to be on search committees and commit to hiring people of color. Cisgendered people need to fight for gender-inclusive bathrooms. People with full time contracts need to work on behalf of those on contingent or part time contracts. People who work in libraries need to model the social changes that are necessary to create truly inclusive workplaces, academic places, communities. This is not a matter of “inviting” people. This is about co-creation. For some of us (she said, ironically) it will be about speaking less, and taking up less space.

What are the explicit policies in your library that are barriers? What does a working day look like? Does it have to be in the building? Do you pay your interns? What do you pay your entry level workers? Do you rely on their “passion” for the profession to smooth over the fact that you can’t pay them enough? Do people starting out have to have a particular credential (that they would have to pay for, that they would have to have done before they even have a job?) Why?

Does your working day have to have certain fixed hours? How is the need for flexibility interpreted? Is it seen as a disadvantage, or a lack of dedication to the job?

What are the unspoken assumptions? Is there an idea of “professional” that doesn’t look like a “nice white lady” in a cardigan or a white man (they don’t have to be nice, remember) in a suit? Do the people you work with know what a microaggression is? Do you hire for “fit” instead of thinking about how to make your workplace fit the people you need to hire? Do you say “we should hire more black people?” “We should hire more people who are Muslim?” Do you talk about race? Do you talk about oppression?

What are you going to do?

Start with not talking about “diversity” anymore.