I had the great pleasure of kicking off this year’s networkED talks at the London School of Economics thanks to the generous invitations of Jane Secker and Peter Bryant. I was asked to address the theme this year: what will learning and teaching look like at the LSE in 2020?

A recording of the event has now been posted here.

I am somewhat allergic to future-speak, but do think that there are some useful ways of approaching the “what are we going to do next” question, and I tried to model myself after those approaches. In particular, I wished my remarks to be grounded in current practice. Too often, I think, futurism is a feint so that one does not have to deal with the complicated present. The future can be shiny and seamless and therefore much more easy to discuss. Also, it hasn’t happened yet. Anyone can be a futurist.

I started with two stories.

The first was the story of 4 students. I saw them walking up to the library gates at a UK University, where I was waiting to be admitted as I did not have a card to get me in. 3 of the students walked through the gates with cards, and the remaining student, as their friends waited just beyond the gates, walked up to the desk and said, “I’m sorry, I left my card inside the library, and can’t get in. I am a student here, please can you check against my name, and let me in?”

The student was let in.

I asked the room: what happened here? The room answered: One of the students was not enrolled at that university, and they did the ID card “dance” to get them into the building, so they could study together.

The moral of that story: Institutional boundaries are more porous to students than they are to Institutions.

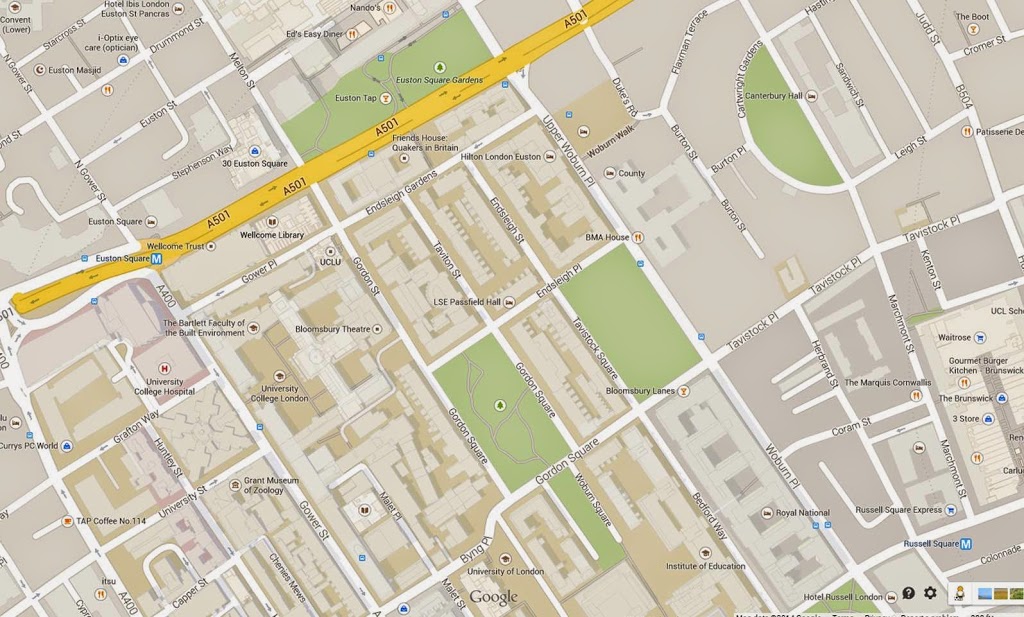

The second story I told was about a student at UCL, in the Institute of Archaeology, who when asked about where he did his academic work, started waxing rhapsodical about the Wellcome Library. He loved that there were huge tables with comfortable chairs, powerpoints all around, “a quiet space that was actually quiet rather than trying to be quiet” and also minus people “waiting for your seat [especially during exam times]” He loved all of the light in the Wellcome. It was his “home” library, not his institutionally-affiliate space.

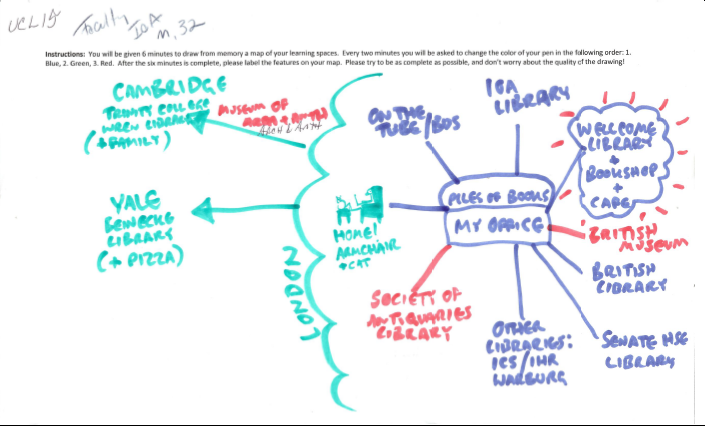

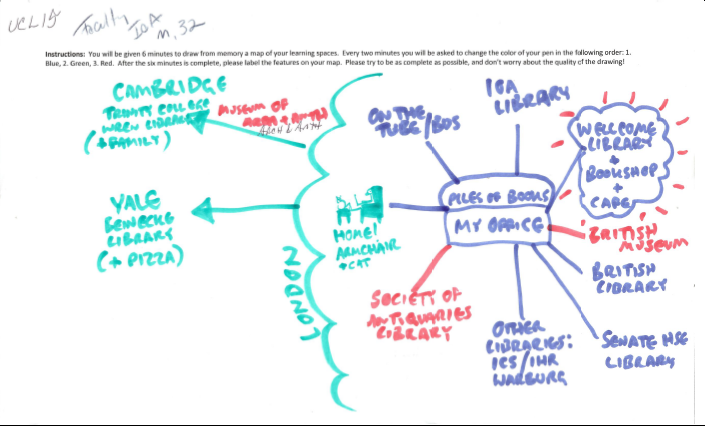

He had a lot in common with a faculty member, also in the Institute of Archaeology, who used the Wellcome Library cafe as his space in which to work, and also to meet with his post-graduate students. That archaeologist’s map of academic work spaces revealed the affection he has for the Wellcome, with lines of significance radiating from his sketch of it in his network of spaces.

Showing the love for the Wellcome Library and Bookshop cafe.

The moral of that story: people’s favorite spaces to work in do not have to be the ones associated with their “home” institutions. Particularly not in a city like London, where such alternate locations are just down the road, across the street, or next door.

What I want to do is ground our sense of what might happen in the Future of Higher Education in the practices of students and staff there right now. This brings me to a conversation about

“experience” and “lived experience, started by my colleague Nick Seaver on Twitter.

Nick got a marvelous response from his colleague Keith Murphy (kmtam), which reads in part:

” for us today to say “lived experience,” aside from its trendiness, is actually signalling something very important regarding a truly ethnographic orientation to the world, one that cares not just about the fact that “something happened to someone,” but that the particular ways in which it happened — how it was understood, felt, and made meaningful”

I’d like us to think about, with all of this talk about “student experience” (which I already have a problem with), what happens if we shift not-so-slightly to a conversation about the lived student experience. What would a consideration of that mean, if we think about the day-to-day experience of being at University in London, and studying for a degree.

In part, my research into learning spaces reveals that the lived experience of students and staff in Higher Education (and elsewhere) isn’t tightly bound by institutional location at all.

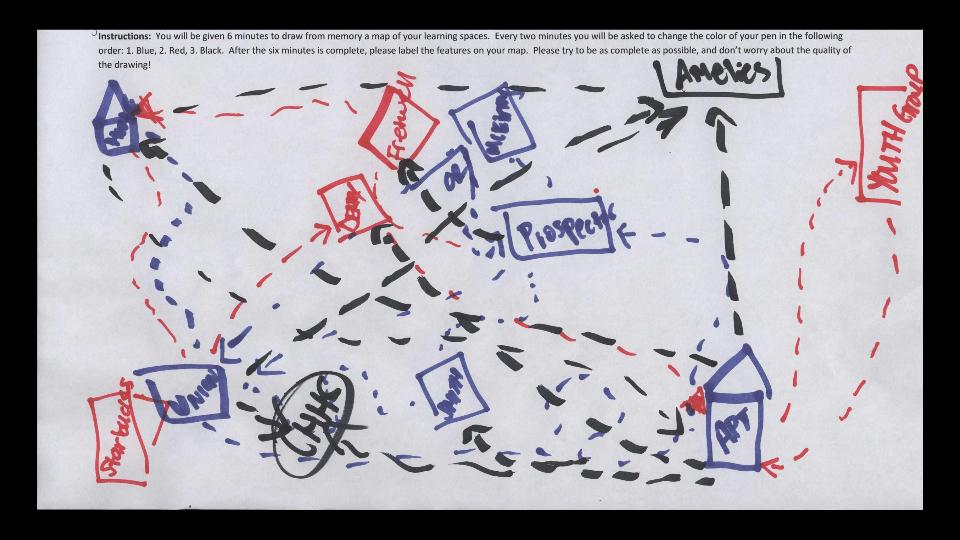

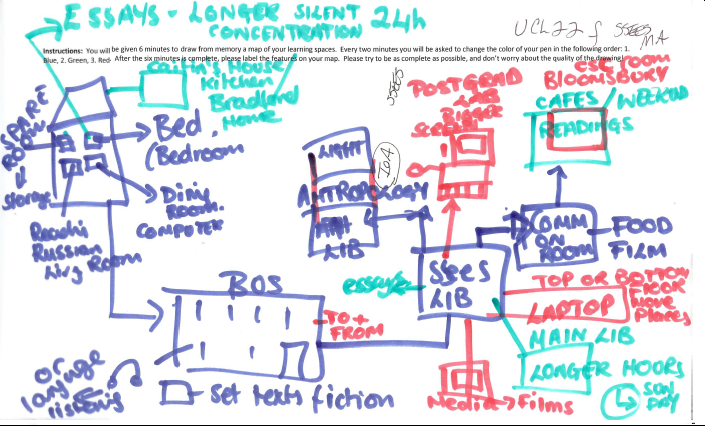

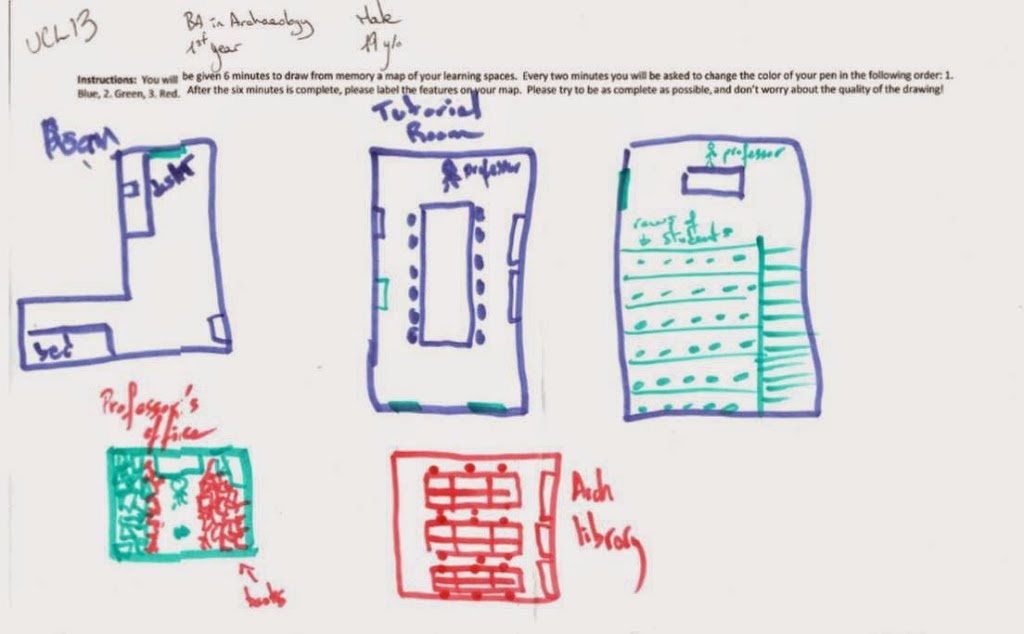

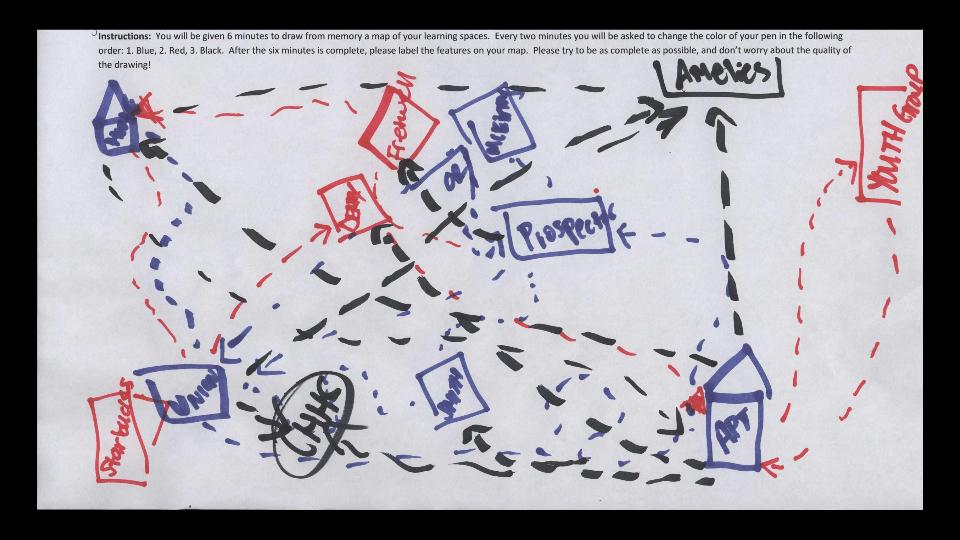

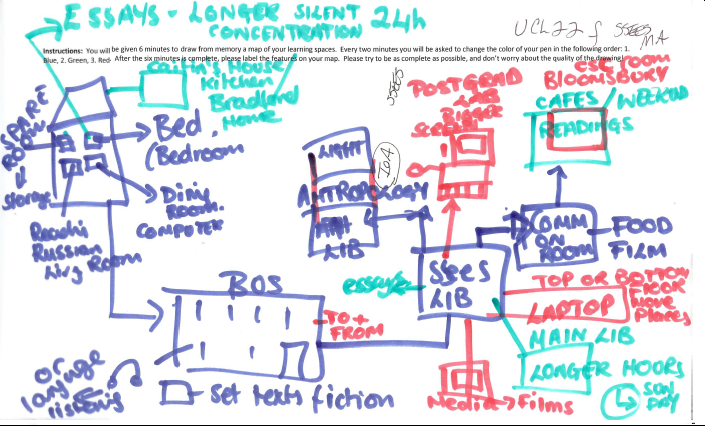

These cognitive maps show how widespread, scattered, fragmented across the landscapes of London and Charlotte these student and faculty learning networks are.

This UNC Charlotte student goes all over town, to her home, the home of friends, to a 24 hour cafe with amazing pastries, and also to the University.

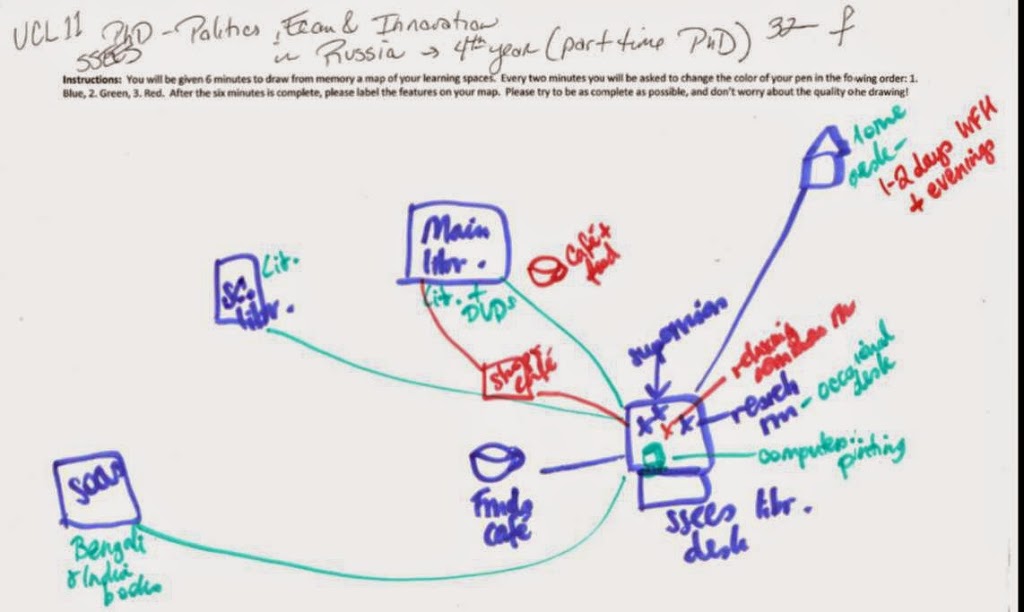

This UCL Student counts as learning spaces her home in outer London, the bus, the Archaeology Library, her “home” Library of SSEES, and Bloomsbury cafe.

Student and other scholars’ lived experience is a networked one–they have personal networks, they are starting to build their academic networks, and they are not neatly bounded. They experience these networks in physical and digital places–these places are also not very neatly bounded, although institutions try to make them so. In practice, institutions are full of people who are Not Of that Institution.

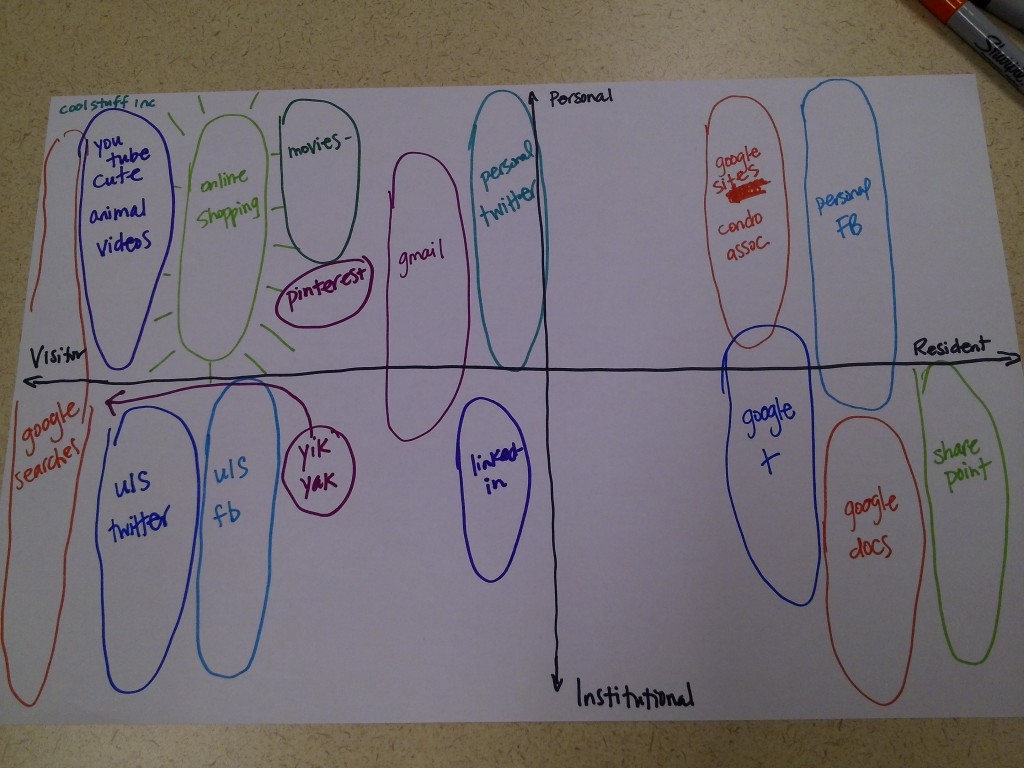

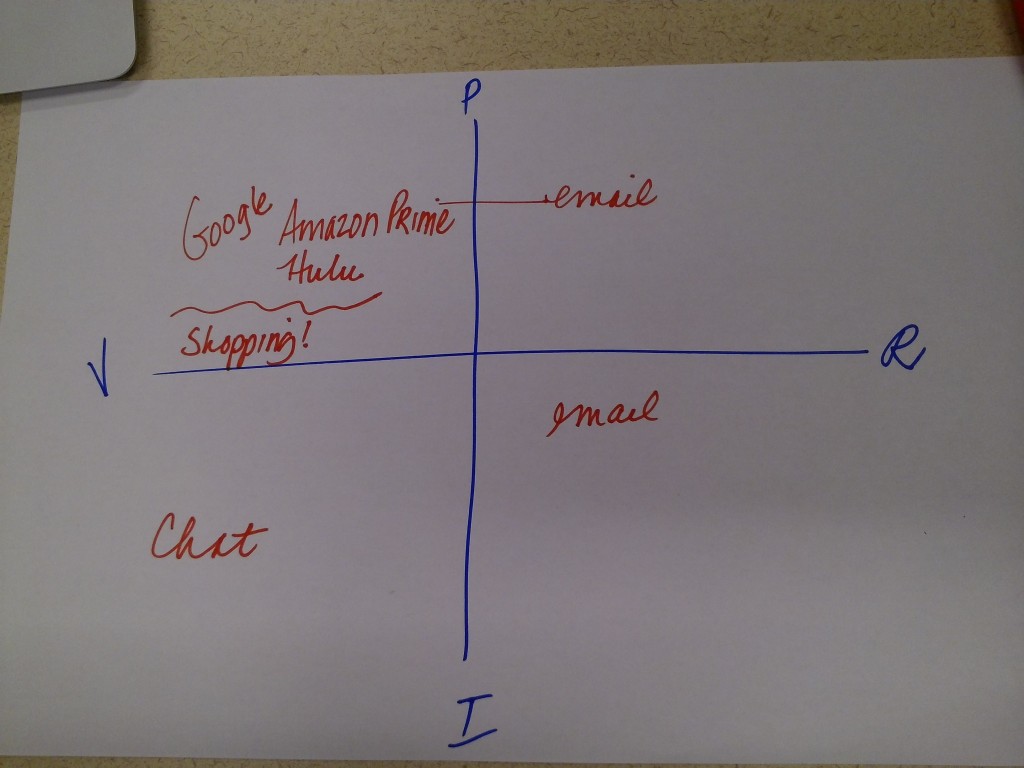

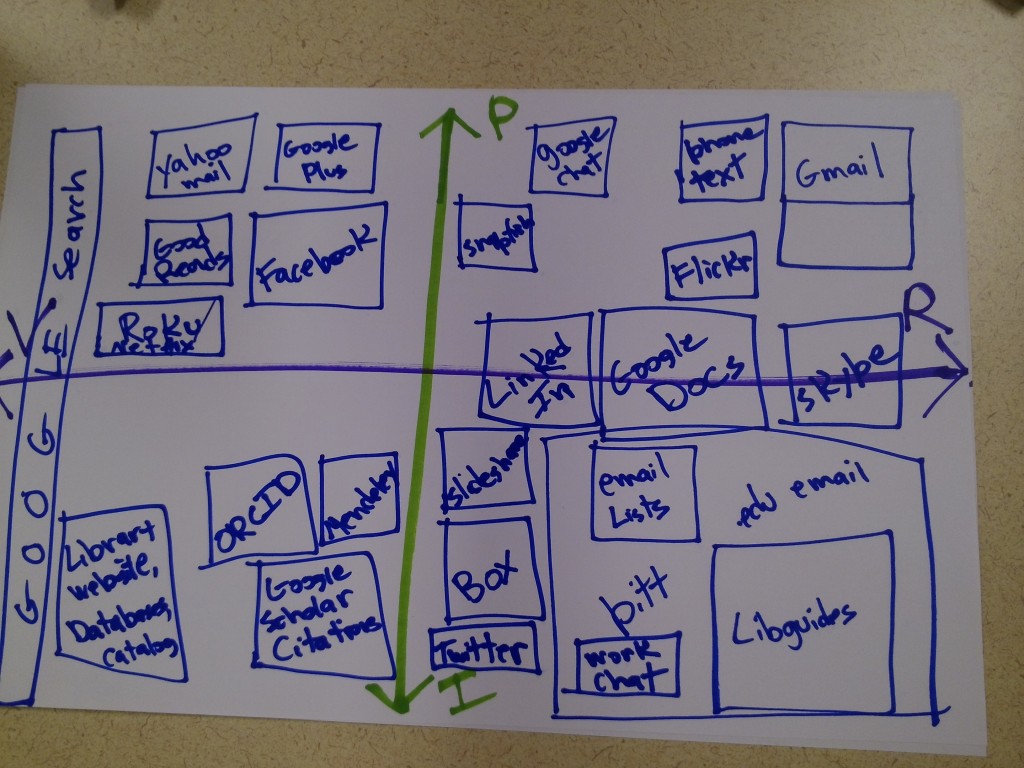

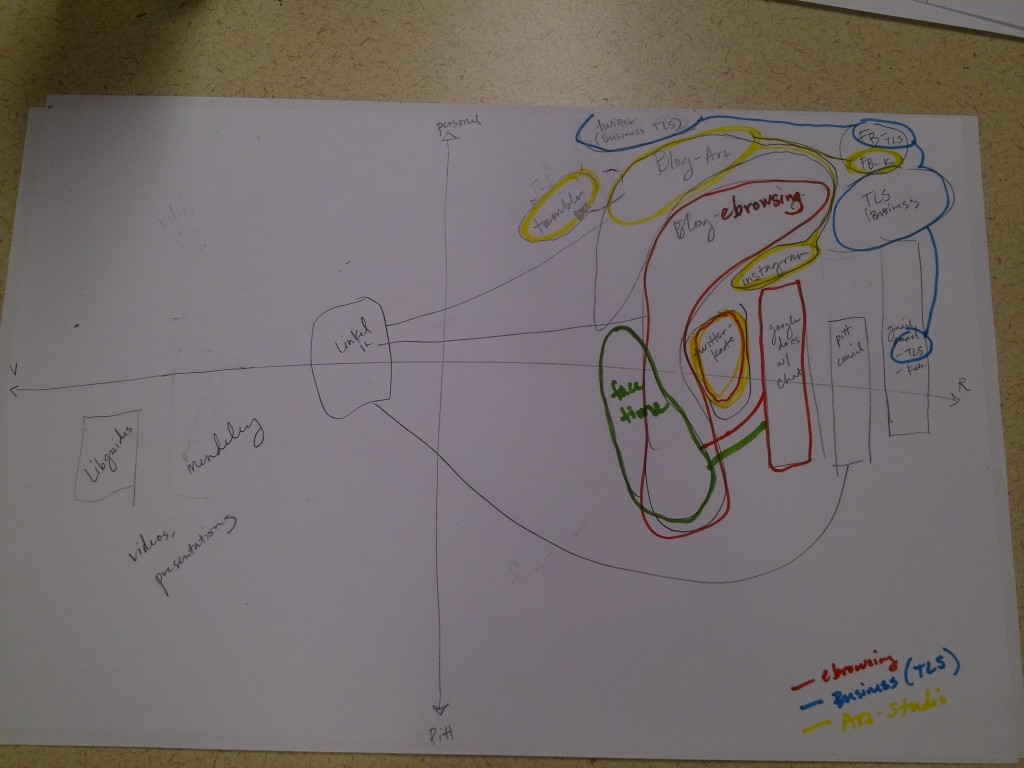

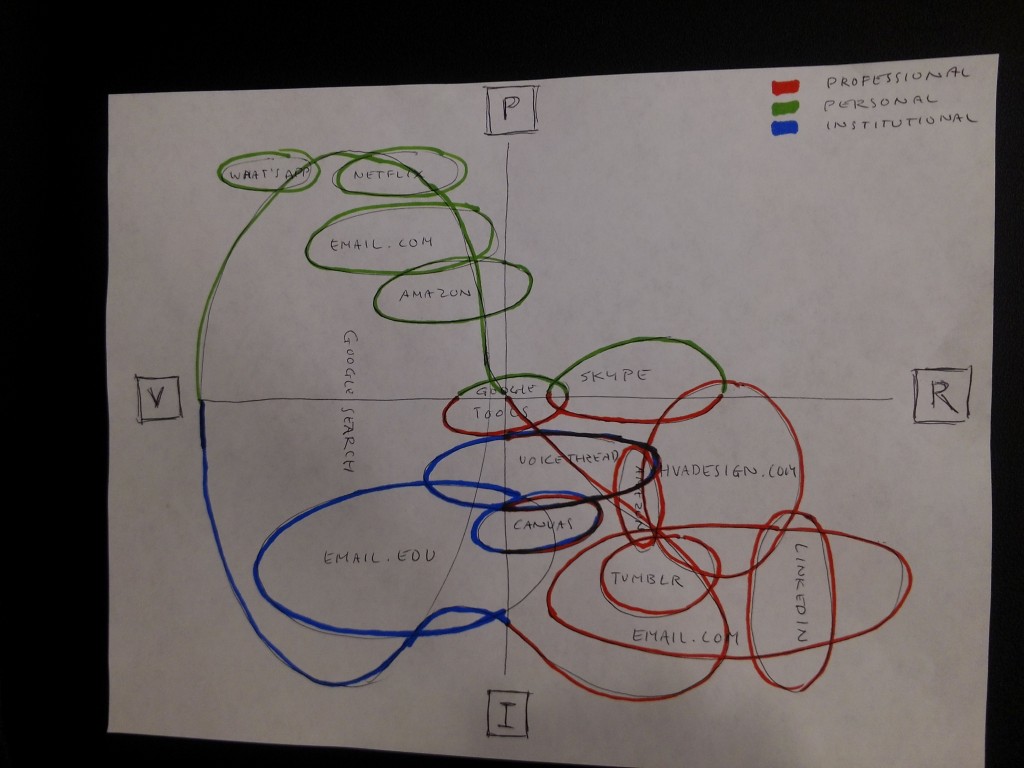

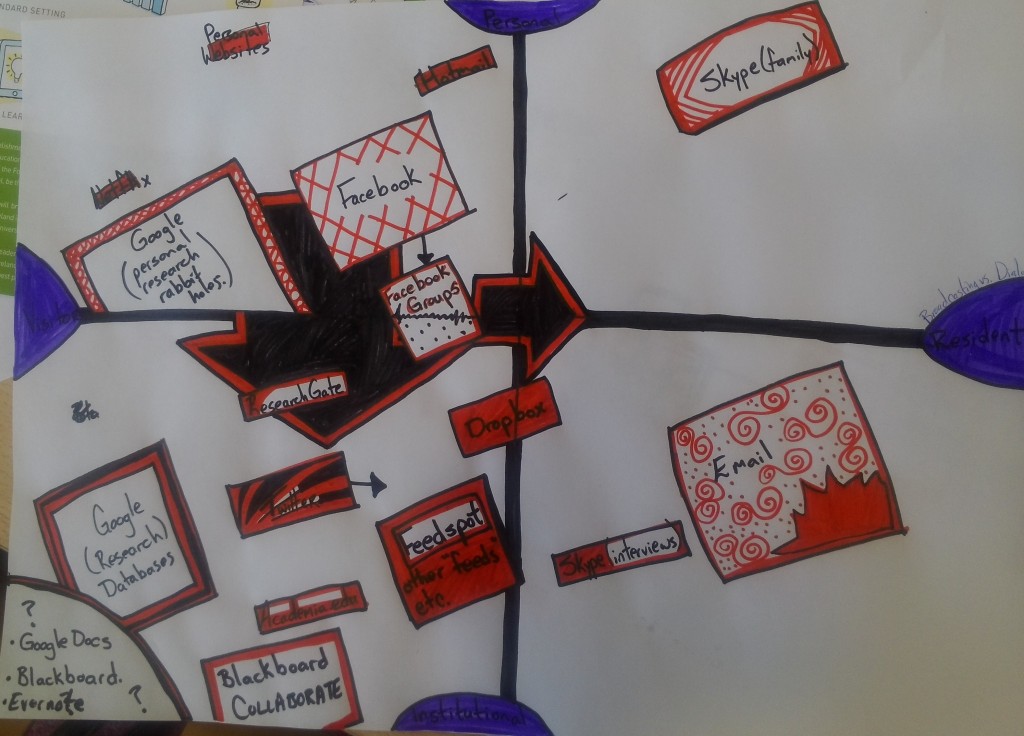

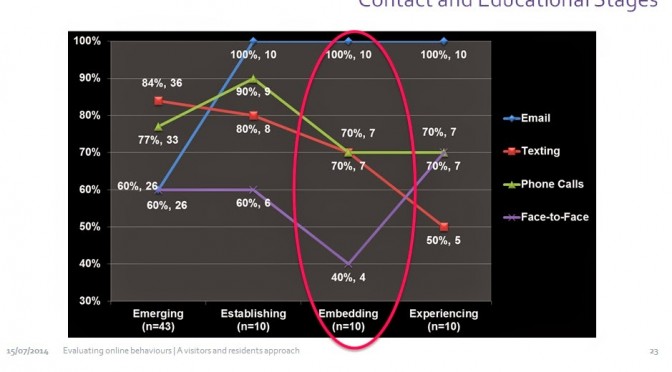

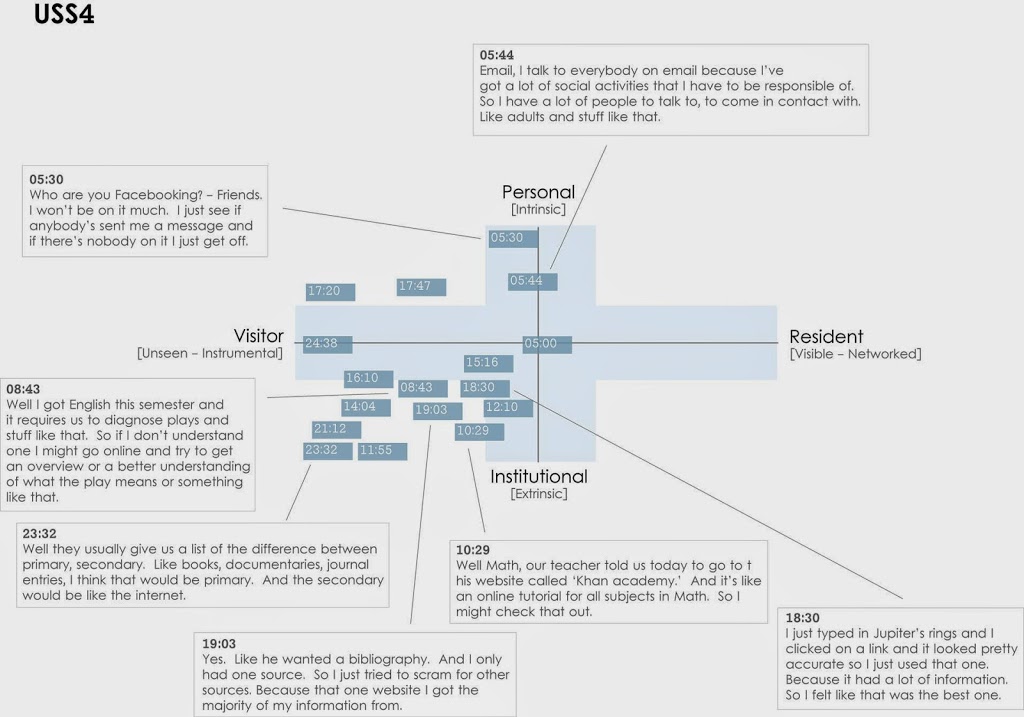

This got me thinking of the work that I do in the Visitors and Residents project, and in particular how we’ve come to refine the mapping process that allows people to visualize their practices. And in visualizing them, they can recognize their practices in important ways, come to grips with how they might like to change things, think about how to continue doing what serves them well. It’s the visualizing that can be the hard part.

Because it’s all well and good to want to talk about how people can do more, engage differently, but you can’t change things if you don’t know the shape of the situation to begin with.

So. If we start from what we know about student (and faculty) practices around learning spaces: they treat them as a network. They do not pay as much attention as institutions do to boundedness (although they do get possessive of spaces).

What happens, then, when we make these networks, created by lived experience, visible?

Contrast the isolated sense of the any institution represented on a map by itself, with the sea of dots that comes up when you Google “Universities in London”:

What can institutions do to make these networks visible, and therefore accessible to more? What could they do to build those networks further, support them with their own resources, go beyond recognizing current practices to facilitating even more? What would that mean for how we think about education, place, and belonging in London Universities?

The whole city of London is treated in many ways like a university. What would it mean to be mindful of that, to move towards that purposefully?

What would happen if we thought of space as a service, the provision and configuration of learning spaces as a thing that institutions can actually do way more effectively than can any individual or private corporation. Starbucks/McDonalds/Caffe Nero/Pret don’t care if their establishments are good for studying–even if they frequently are because of free wifi, comfy chairs, and access to snacks.

Fundamentally, this is a Common Good argument.

Because our students encounter barriers all the time. In a context where they need more space, not less. And in a context where universities themselves are acutely aware that they cannot provide all that their students need. What about leveraging the network of London spaces to be a connected set of spaces, powerful in their mutual awareness, profound in their potential to connect students to other resources, other places, other people. This is the work of education: preparing our students for the diversity of experiences that will come their way. It is more than our work, it is our responsibility.

What problem are we trying to address when we throttle access? Is it people we don’t want in our spaces? Is it discomfort of people who “belong?” Is it limited resources that we want to conserve for “our community?”

People who work in libraries are used to thinking about who gets to be in and out of the space. Public libraries in particular struggle with access: who is in the building? who uses services? how can the library serve them? I think here about about homeless people in public libraries in the US, and policies such as limiting the size of bags people can bring into libraries, which target these populations of people who often have nowhere else to go. Why are the homeless a problem in the library? The problem of homeless people in the library is about so many other things. They are matter out of place. It’s about discomfort, housekeeping, mental health, access. These problems are not solved by banning people. Savvy libraries such as the San Francisco public library, and also the public libraries in DC, have moved to hire social workers, have job seeking centers as part of their library services. They are taking the broader view of what their responsibility is to the people in their spaces.

Likewise London universities concerned about resources for their own community won’t garner the resources they need by banning certain categories of people from their locations. I would argue rather that they decrease the access of their community members to the value of London. Let’s remind ourselves again that chopping London into silos goes against the very thing that can make big cities so marvelous.

If Institutions have a reason for being in London, then why would they protect their students from the London experience?

The point was made in the room, quite rightly, that of course many London students are in London because they are from that city, not because they have “Come for the London experience.” And it’s also very true that not all students experience diversity and difference as something positive to explore, but as members of communities who are victimized and marginalized by perceptions of difference. In those cases, many students choose to go to university to be with people among whom they do not have to explain themselves, to experience being with others who are “just like them.” And who might not thank totalizing agendas that valorize “diversity” as something that people should go out and find for personal growth.

I think there is still an argument to be made for networked universities to connect because it provides spaces for students to encounter each other (and all of their similarities as well as differences). And in being networked with each other, universities can continue to provide places for students to come back to, institutional homes where they gain comfort, and can eventually contemplate ways of feeling safe even as they confront discomforting situations.

Learning places are not monolithic, not in physical space, nor should they be in digital places. But digital tools can be used to connect physical spaces, to link them and thereby create something even better.

Academic libraries, for example, are starting to think about themselves not as The Learning Place on campus but as a part of a network of learning places, and this is informed by work like mine that shows the lived experience of university students. Cambridge University is working to build digital tools to make the network of spaces visible, in particular with their SpaceFinder app, which makes it possible to visualize (and so, consider accessing) a wide range of spaces in and around Cambridge University, not just institutional ones.

I ended my talk with a question, What would this look like for all of London?

There are already digital things that network universities in the UK–Eduroam was brought up by the room, and I think it’s a great example.

I did surprise myself rather far along in the discussion with the realization that I am in fact making an open-access argument about the physical resources of universities in London. I stand by that. I think it’s worth exploring.

I was also surprised by the lack of discussion in the room around security issues (perhaps that is my bias coming from the US, home of Security Theater). I was pleased at that lack, it left time for talk about curriculum and education, and class differences that affect how various HE and FE institutions have (or don’t have) resources.

The discussion in the room was wide-ranging,And people paused really thoughtfully before digging into a conversation that was shot through with practical and ideological concerns. I was so pleased to witness and participate.

https://twitter.com/lselti/status/644159059181064194

https://twitter.com/authenticdasein/status/644164802479308800

https://twitter.com/RogerGreenhalgh/status/644165931804065792

https://twitter.com/authenticdasein/status/644166875807674368

https://twitter.com/DonnaLanclos/status/644271220498767872