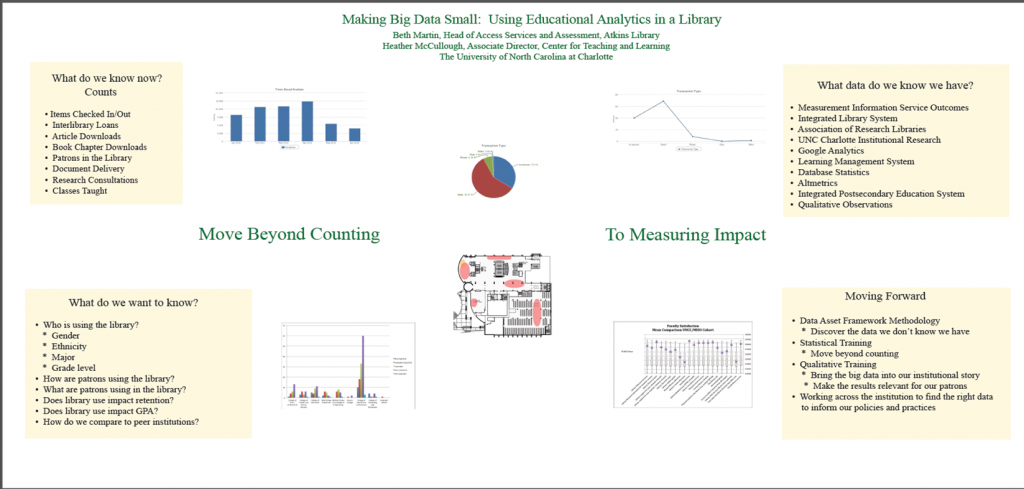

Recently my colleagues Beth Martin and Heather McCullough presented at Educause on our assessment agenda in Atkins Library. I love this work, I am delighted to work with them here at UNC Charlotte. I’m sharing the poster here because I think it’s terrifically important to get as many voices as possible into the conversation about what assessment is, could be, and should be for, in Academic Libraries, and in Higher Education generally. I have blogged about the Mixed-Method, Interdisciplinary library before, and I think that this poster is a nice example of how we are going to operationalize that at Atkins, with partnerships within and outside of the library.

I’m including a summary in this post of their main points, and a link to their poster.

Educational Analytics and Libraries

Educational Analytics in this context encompasses both Learning Analytics and Academic Analytics.

Learning Analytics focuses on data about the learning process while academic analytics focuses on data about the institution.1

UNC Charlotte Atkins Library is putting together an analytics initiative that will explore both learning and academic analytics through a library lens.

The Initiative

| What we do now | What we want to do | How we will move forward |

| Count items and people | How are patrons using the library? | Discover what data we have using the Data Asset Framework Methodology2 |

| Qualitative space assessment | Explore impact of services across gender, race, ethnicity, major, grade level, etc. | Statistical training

|

| Impact of library on retention | Qualitative research training

|

|

| Impact of library on GPA | Work across the institution using data to inform policies and practices | |

| Compare to peer and aspirational institutions |

The Tools

- Measurement Information Services Outcomes (MISO)

- National Survey of libraries used to compare across institutions as well as inform internal practices

- Integrated Library System

- Main library system that stores usage data

- Association of Research Libraries data

- National library data

- UNC Charlotte Institutional Research

- Data analysis of all institutional research

- Google Analytics

- Learning Management System

- Data on student usage

- Library Database statistics

- How are scholarly articles/books being used

- Altmetrics

- Social and collaborative nature of institutional research

- Integrated Postsecondary Education System (IPEDS)

- Qualitative studies

- Space use

- Classroom use

- Student Learning Outcomes analysis for library instruction

The project is in the first stage of the Data Asset Foundation methodology, which is scheduled to finish this December. Once we have a clear picture of the available data we will look at our initial research questions to determine what we can explore with the available data and what data we may need in the future.

Contact Information

Beth Martin, Head of Access Services and Assessment

Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte

sarmarti@uncc.edu

Heather McCullough, Associate Director

Center for Teaching and Learning, UNC Charlotte

hamccull@uncc.edu

Citations

- Penetrating the Fog: Analytics in Learning and Education. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2014, from http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/penetrating-fog-analytics-learning-and-education

- Data Asset Framework | Digital Curation Centre. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2014, from http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/repository-audit-and-assessment/data-asset-framework