I was invited. This time I got invited to Aotearoa, New Zealand, and I am so grateful for the opportunity. I had never been to that part of the world, and this part of library-land was also new to me (even as I had been following some library folks there via Twitter).

The Lianza conference was full of amazing people, it’s a fantastic community, I am so pleased I got to spend time in that room, filled with enthusiasm and criticality, public as well as academic librarians. You can watch keynotes and sessions recorded at Lianza and I recommend you watch them via their site, here. If you want to watch mine (including the Q and A, as well as the song they sang to me after I was finished!), that’s here (you’ll be asked to register for the site).

Thank you to Viv Fox of PiCS for sponsoring me, to Kim Tairi and David Clover for excellent advice while writing my talk, and to the scholars whose work I consulted in the course of putting this together (I tried to link within the blog, but have also put together references at the end of this). Thank you to Paula Eskett, and to the entire conference program committee and team for working hard to make me feel comfortable and welcome.

This is, as best I can recreate, the text of my talk.

Tēnā koutou katoa

(Greetings to you all)

I am from California, near the Pacific Ocean, and also near the high desert in the south. I lived in Chumash, Ohlone, and Yuhaviatam land.

I live in North Carolina, in the piedmont, between the Appalachian mountains and the Atlantic ocean. It is Catawba and Cherokee land.

My father’s family is from Louisiana, along the Bayou Teche, we are Cajun. We were settler people, on Chitimacha land. My PaPa was beaten for speaking French in school. My MonMon never learned to read.

My father is Harold John Lanclos

My mother is Judith Cameron Lanclos

I am Donna Michelle Lanclos, named after a Beatles song and my mother’s college roommate

Tēnā koutou

Tēnā koutou

Tēnā koutou katoa

Kia Ora

Thank you for inviting me, thank you for bringing me here. I am so grateful.

I am at the mercy of people’s invitations, personally and professionally, I get to be where I am because someone, at some point, let me in.

This is true for anthropologists generally–we get to be where we are, to do the work we do, because someone lets us in.

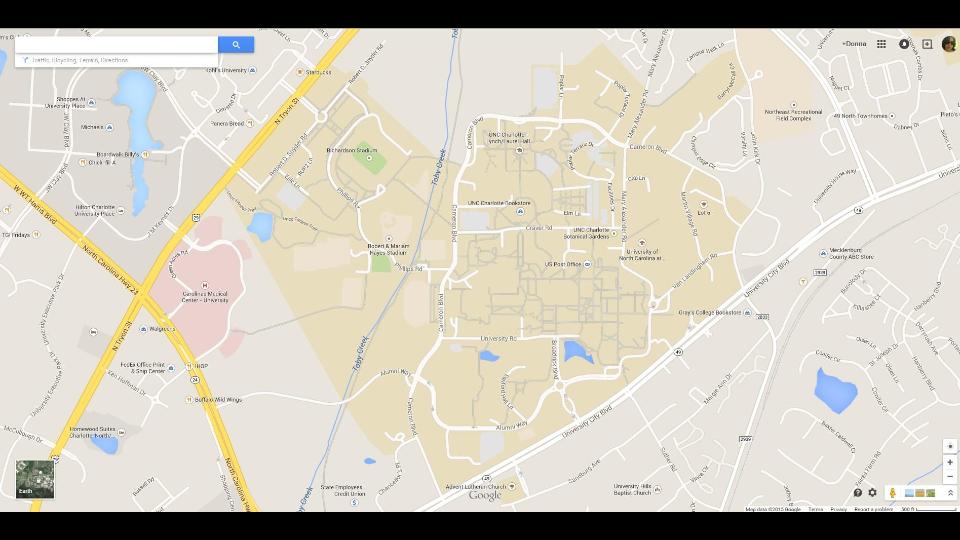

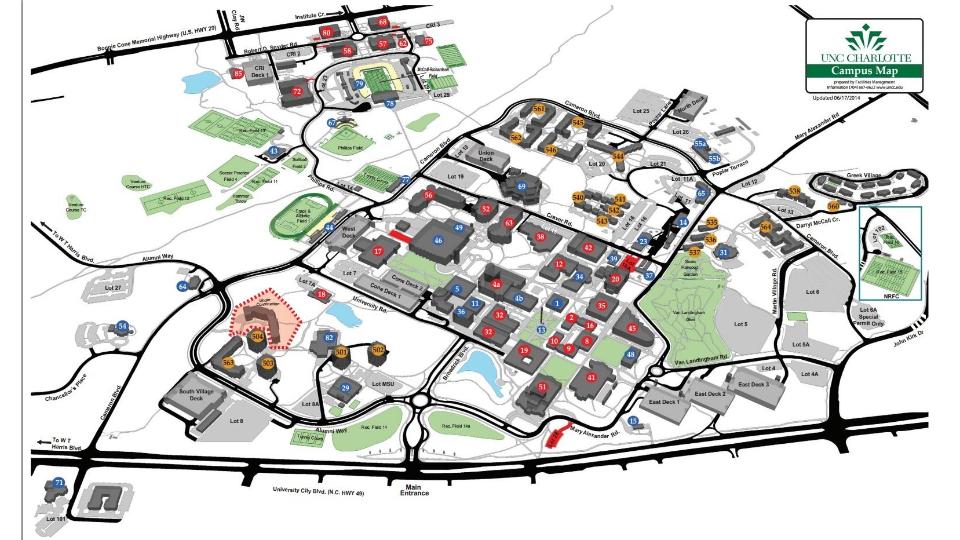

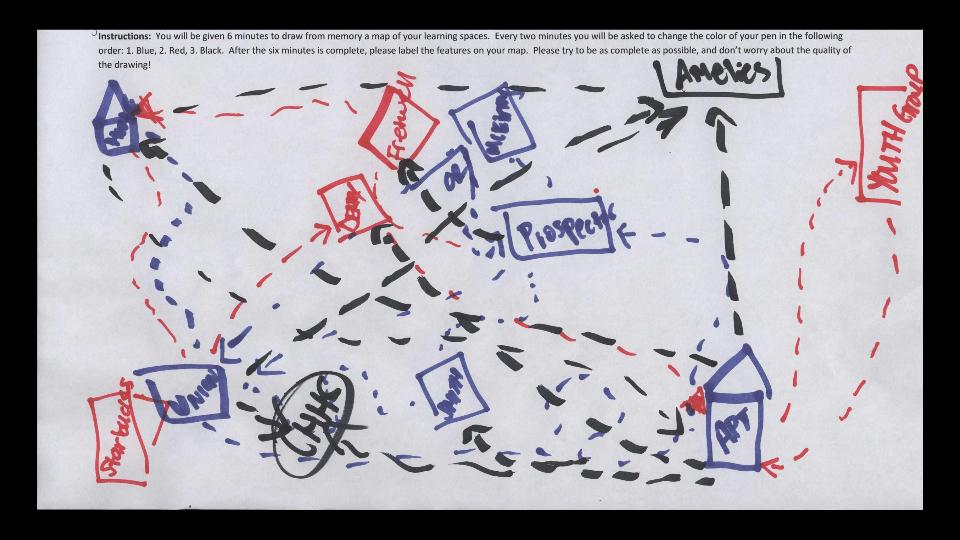

(I talked about my work at UNC Charlotte here in the talk, you can read more about it elsewhere on my blog here. I made the basic point to the Lianza audience that my work is an anthropology of academia, my responsibility is to research and analyze the logic, the motivations, and practices of academics)

Once anthropologists are let in, then, we do the work of stories.

We collect stories.

We listen to stories

We interpret stories

We put different stories together.

And then we tell stories. We tell our own, as a way in, we tell the stories of other people, because it is our work, the work of making the “exotic familiar” (and, the familiar exotic). When people talk about qualitative work, especially in contrast to quantitative work, they often invoke stories, they talk about the work of stories. Some people use story as an epithet, synonymous with anecdote (also meant as an epithet). But, stories are data, stories are information, stories are ways of representing and interpreting reality.

I started thinking about this talk with the framing of stories in part because I realized early on the link between colonial New Zealand (especially ChristChurch and Canterbury) and Chaucer. Maybe it’s only a link in my mind, it made me think immediately of my mother, who was an English major at university, and who kept her copy of Canterbury Tales in our house when I was growing up.

When I was in my last year of High School, my teacher taught us about Chaucer, and his Canterbury Tales. We had a textbook that excerpted several of the tales–the Miller’s tale, for example. But also, and this was formative for me: The tale of the Wife of Bath. I had my mother’s book, and I could see that the tale of the Wife of Bath was very very different from the one we were presented in our textbook. There were words in the college version that did not show up in the high school version.

I was the kind of student who wanted to ask questions about that.

So I did.

I brought my mother’s book to school, and as my teacher was having us read the bowdlerized story of this woman who had many husbands and a lot of sex, I was raising my hand on a regular basis.

“Mr Taylor, that’s NOT what it says in MY book.”

I was not my teacher’s favorite student in that moment, but the story was different! I wanted what I thought was the “real” story, not the one packaged as appropriate for children. Chaucer told a story about storytelling, the way my teacher was using it taught me a great deal about the power of who controls stories, and what different versions can do to your sense of reality.

I am also a folklorist, and this awareness of multiple versions of the same story, this is part of what defines something as folklore. And folklore materials are another kind of data, there is meaning in the stories. There are always versions, and meaning within that variation. Think of Cinderella, of Little Red Riding Hood; who tells the tale informs what tale is told. Sometimes the huntsman rescues Little Red Riding Hood. Sometimes she rescues herself. Sometimes the stepsisters live happily ever after with Cinderella. Sometimes they lose their eyes to birds as well as parts of their feet to the knife.

I am an anthropologist.

I study people.

I am located in a discipline with a troubled history, and a collusion with colonialism that we can never shake, and we have to acknowledge.

Social Anthropology in the UK in the early 20th century was literally tool of the man.

After his initial fieldwork in the 1920s among the Azande in the Sudan, E.E. Evans Pritchard was hired by the Anglo-Egyptian government–the context for this hire was the conflict that the colonial government had with the Nuer people in the 1920s.

Colonial officials thought if they had more information about the people they wanted to control, they would be able to do so more effectively, and wanted anthropological knowledge to be a part of this mechanism of control. Control did not necessarily happen, but this was certainly the intent.

Smithsonian Archives, ” Franz Boas posing for figure in USNM exhibit entitled “Hamats’a coming out of secret room” 1895 or before”

Franz Boas took up anthropology as his life’s work after his previous academic life as a physicist, who wrote a dissertation on the color of seawater. He is known as the Father of American Anthropology, and a champion of anti-scientific racism. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the “extinction narrative” had already quite caught hold, and Native American and First Nations groups were the object of study at least in part because they were framed as “disappearing”

19th century anthropology co-occurred with the systematic dispossession, persecution, and killing of indigenous peoples, the “salvage anthropology” that followed in the 20th century referred to “disappearing” people as if they were fading, not being colonized and displaced by white settlers.

First edition cover for Ruth Benedict’s ethnographic treatment of Japanese culture. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/9/90/TheChrysanthemumAndTheSword.jpg

In the mid-20th century, during the second World War, anthropological knowledge was leveraged as a way to better understand (and, it was presumed) and so control our conquered enemies, the Japanese. Ruth Benedict did “armchair anthropology” during WWII, and her resulting work, the Chrysanthemum and the Sword, informed the occupation strategies by the US of Japan after the war.

These are not the only examples of anthropological knowledge being taken by governments and other policy makers as part of their toolkits for control. The debate within anthropology over the role of the knowledge it accesses, communicates, and creates in the military, and in government, erupted strongly during the Vietnam War, and again with the US war in Afghanistan since 2001.

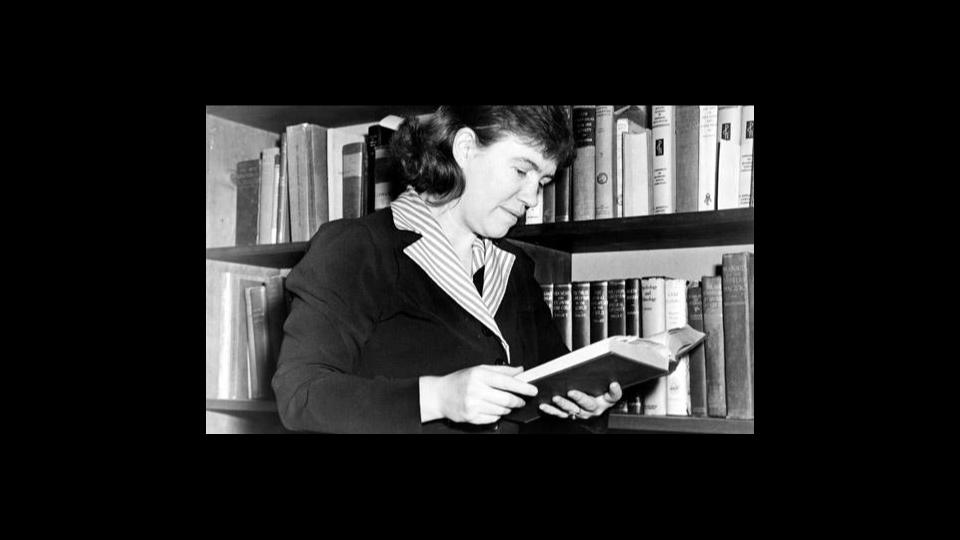

I keep coming back to the example of the work of Margaret Mead when I talk about the potential of anthropological work. There are problems with whose stories she told, and for what purpose, but her purposes shifted from those of institutional control to one of understanding, and it is for this that I value her work, in Samoa and also in Papua New Guinea.

Margaret Mead. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/24/Margaret_Mead_NYWTS.jpg

Her intention, as a student of Boas and Benedict (among others), was to make the unfamiliar familiar. And also, to make the familiar unfamiliar, to question the practices of her own culture with regard to, for instance, adolescence and childrearing. She brought what she learned from other cultures back to her own, as a way of advocating for change, as she considered many practices in the US to be toxic. She used other cultural practices to feed her imagination, for what else might be possible.

Why am I telling you this? Many of you probably know the colonial history of anthropology, the problems and pitfalls baked into its disciplinary history.

So let’s talk about Libraries—This is Andrew Carnegie, founding the Carnegie library in Waterford, Ireland.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/49/Foundation_stone_of_Waterford_Free_Library.jpg

These libraries (in the US, the UK, and also in New Zealand, among other places) were ways for Carnegie to impose his idea of what communities “should have” as expressed in a particular structure of knowledge and respectability. The leaders who petitioned Carnegie in the late 19th and early 20th century to have these libraries built in their communities were buying into that particular kind of respectability. They wanted to be associated with that respectability, and the power associated with it.

This is Libraries as colonizing structures, structures shot through with orientalism, white supremacy, and settler colonialism.

The problem with these, with any colonizing impulse (OK, one problem among many) is the assumption that if you don’t put a library there, if you don’t establish a colonial government, there won’t be anything. It ignores what is there.

Aotearoa pre-dates New Zealand. There were people, long before there were libraries.

In my own work, I see the colonizing impulse in libraries in two specific ways.

The first is the reaction I occasionally get when I present on the logic behind student or faculty behavior that might be confounding to library professionals (eg, using SciHub, citing Wikipedia, not putting their materials in the Institutional Repository).

I talk about motivations, about the competing and conflicting messages that people get around information, and the ways that some things (using ResearchGate, for example) make sense to individuals even if those choices, from a library perspective, are less than ideal. And I am asked:

“So how do we get them to change their behavior?”

Fortunately, that’s not my job. But if that’s the end point, I’ve failed a bit in what is my job, that is, generating understanding of the underlying logics behind human behavior such that the thought of what might be “best” can fall away, to allow for a wider range of possibilities.

The second reaction is one that I sometimes get when I propose open-ended investigations of human behavior in universities. Projects such as the Day in the Life study, which was pitched as broadly exploratory, without particular questions beyond, “what is student everyday life like at universities in the United States?” And I am asked:

“How will this help me solve X problem?”

In this case, I don’t mean to be dismissive of a particular problem, but problem-solving is rarely the point of exploratory research. Gaining insight, creating a sense of a bigger picture, revealing context that helps with understanding, these are all things that such research can generate, but those things are not aligned with the metrics that libraries are beholden to, the quantified existence that higher education and other municipal entities are increasingly made to endure. What value? How much? What is the ROI?

I cannot answer that. I don’t want to.

You don’t do anthropology among students and faculty so that you can manipulate them do to library-style things

You do it so that the library can more effectively shift its practices.

The impetus for change should come from libraries, not from “users” How do you listen? How do you change what you’re doing? How do you create inclusive spaces? Spaces that welcome whether someone has been invited or not?

How do you find out the stories behind the people in your library? How do you find out stories about your community, whether they are in the library or not? Anthropology can be one way. In particular, the anthropology that invites you to de-center yourself, your perspectives, your biases, and take on the priorities and perspectives of the people you are interested in learning from.

I want to contrast the “understanding people to control them” anthropological heritage from the “understanding people to connect with them” piece that I think should actually be the goal. Trying to get libraries to understand the difference is crucial–we don’t want to be the colonizing library. No matter how much power librarians don’t think they have, you have so much more power than the people who are in there using the library. So, you have a responsibility to be careful.

In the long history of colonialism and anthropology, there is a thread of interrogating practice without valuing it, and for the purposes of control. We should rather be engaging with communities via research, exploring in ways that are about generating big picture insights, not “action research” problem solving and repetitive projects.

What are the stories we need to hear, and retell, from the people in our libraries, in our communities, whether they are in the libraries or not?

Anthropological fieldwork can’t help you if you’re still only interested in telling the library’s story.

So what can we do? How can we reframe? I’d like to suggest a couple of things.

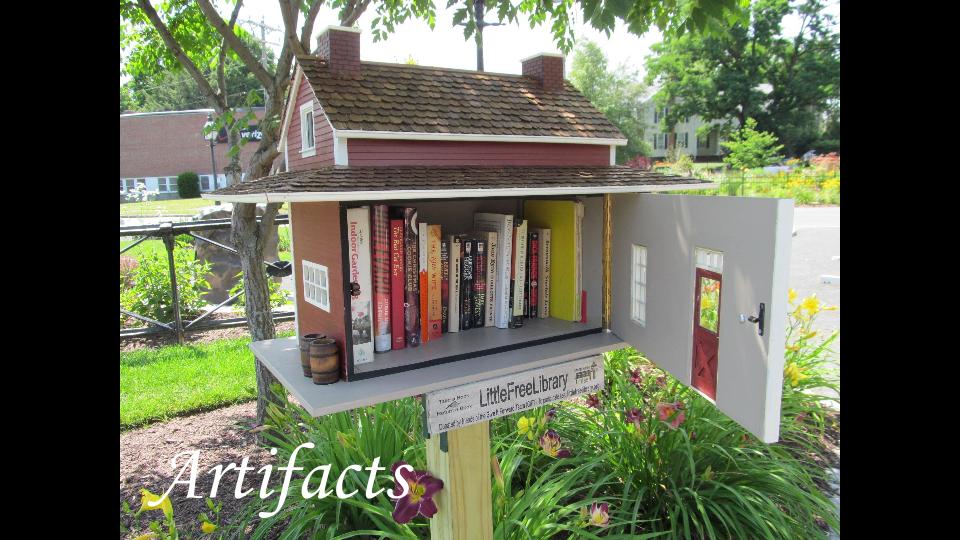

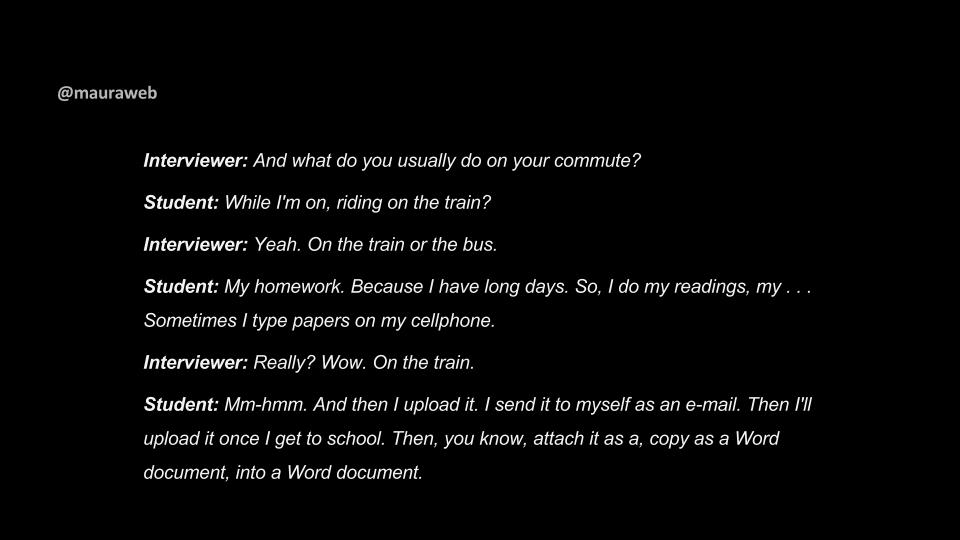

First: Syncretisim, a concept which might be one way around the solutionism that I see so much in libraries. In my experience I have encountered syncretism most in anthropology of religion, to refer to that cobbling together that people do around beliefs and practices, especially in colonial situations, but also in contexts of migration. Population movement and contact brings people together from different places, and the power relations that also inform that context result in not a seamless blending of religious practices, but a seaming together, a picking and stitching so that you can see the original component parts in the something new that emerges.

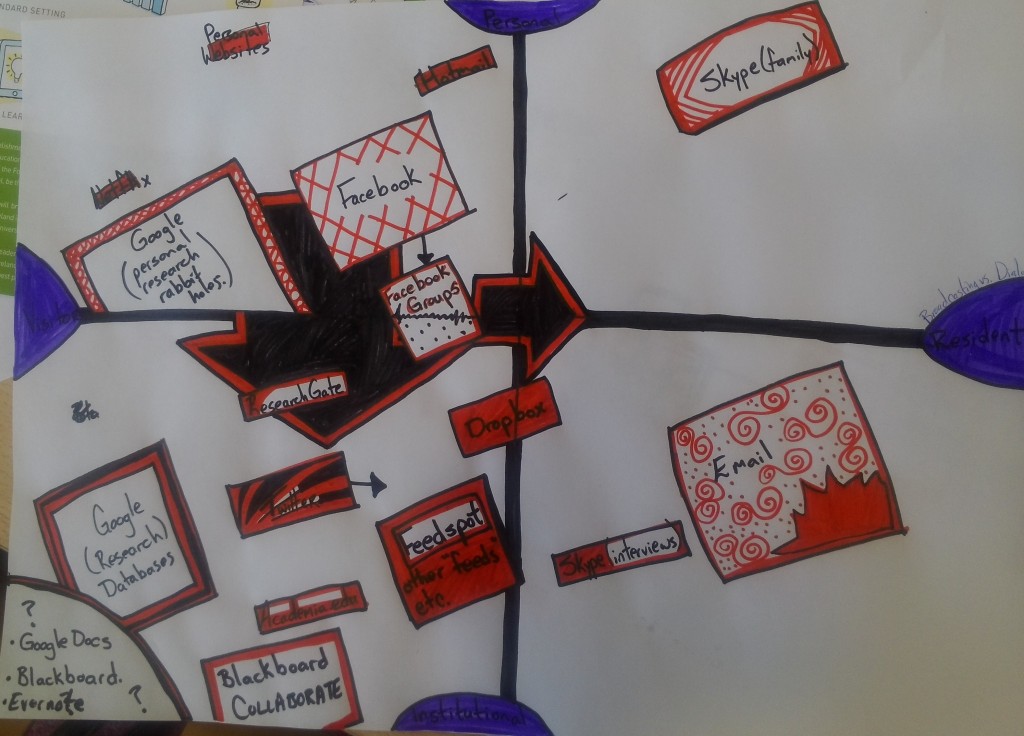

I think syncretism emerges in the ways that people approach libraries these days. They come to libraries, public and academic, with an already formed set of practices around digital and information. When they come into contact with library practices, their own don’t suddenly disappear–they make room for new practices if they serve them, and incorporate them into their own.

As educators in libraries we have a reasonable expectation that we can teach people in our communities new and useful things about information, about research, about reading and interacting with all of the resources that libraries can serve as a portal to. We should also expect to be taught by the people in our communities what libraries (and the content and expertise within libraries) are for to them.

Second: Decolonizing. Breaking down the power structures that are barriers to inclusion in institutions such as libraries. Libraries, like anthropology, emerge from and reproduce colonizing structures. They “other” in defining who belongs and who doesn’t, what “fits” and what doesn’t. And here I am particularly indebted to the work of Linda Tuhiwai Smith, nina de jesus, April Hathcock, and Fobazi Ettarh.

I also want to recognize that this is not a new idea to New Zealand, even as there is still clearly work to do.

If we acknowledge that libraries are colonizing structures, we should ask what it would mean to not have the library define itself, but to listen to the people who are in the library, but not of the library? How can we make space, fight for space so that the definition of library emerges from the community in which the library sits, so that the library becomes indelibly the community?

We need to move away from the language of “user” because that privileges the buildings and structures of libraries. I want to follow Chris Bourg here in emphasizing that what our responsibility is, is to our community. This word “community” does an end-run around “users”–because the construction of user suggests that the significant people to libraries are only those who are in their buildings or in their systems. But our responsibility is to our community, whether they are “in the library” or not..

I want us to think of and speak about and emphasize Libraries as a social place, with a mission that is beyond content.

Who is in your library? Who is of your library?

Public libraries have a much better handle on this than academic libraries. There’s far less “how do we get them to library the way we want them to” in the air in public libraries, and we in academic libraries would do well to pay more attention. This, too, anthropological approaches can help with. But only if we follow the line of anthropology that moves away from colonizing structures.

(What is the most important thing in the world?)

He tangata, he tangata, he tangata

(It is the people, it is the people, it is the people)

References:

Bourg, Chris “Feral Librarian” (blog) https://chrisbourg.wordpress.com/

de jesus, nina. “Locating the Library in Institutional Oppression. In the Library with the Lead Pipe.” (2014). http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2014/locating-the-library-in-institutional-oppression/

Ettarh, Fobazi “WTF is a Radical Librarian Anyway?” (blog) https://fobaziettarh.wordpress.com/

Hathcock, April “At the Intersection” (blog) https://aprilhathcock.wordpress.com/

Johnson, D. (1982). Evans-Pritchard, the Nuer, and the Sudan Political Service. African Affairs, 81(323), 231-246. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/721729

Leonard, Wesley. “Challenging” Extinction” through Modern Miami Language Practices.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 35, no. 2 (2011): 135-160.http://uclajournals.org/doi/abs/10.17953/aicr.35.2.f3r173r46m261844?code=ucla-site

Lofland, J., & Lofland, L. (2001). Handbook of ethnography (pp. 1-7). P. Atkinson, A. Coffey, & S. Delamont (Eds.). London: Sage.pp.66-67

Prescod-Weinstein, Chanda “Making Meaning of ‘Decolonizing’” Medium, Feb 20, 2017 https://medium.com/@chanda/making-meaning-of-decolonising-35f1b5162509

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books Ltd., 2013.

Te Ahi Kaa, Whakatuki for 26 May 2013, Radio New Zealand http://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/teahikaa/audio/2556269/whakatuki-for-26-may-201

Unsettling America (blog) https://unsettlingamerica.wordpress.com/