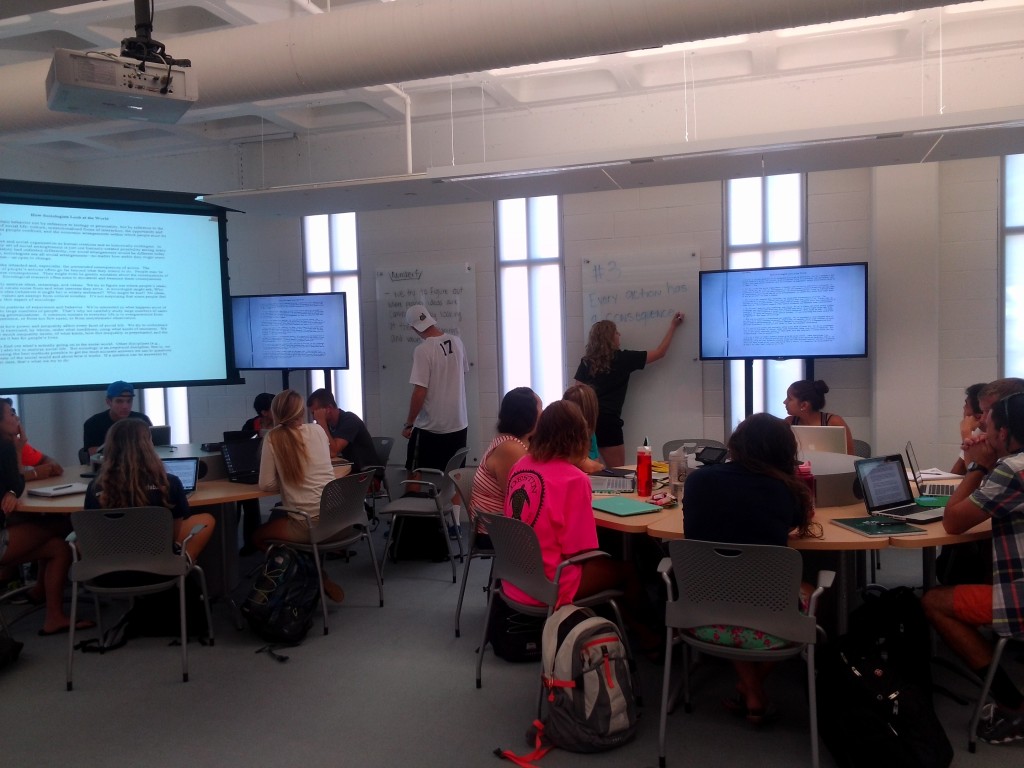

The Room (and The WALL) of UXLibs, St. Catherine’s College, Cambridge. Photo by Jamie Tilley, see full Flickr photostream at https://www.flickr.com/photos/132033164@N06/with/16842774026/

I have never been to a conference like UXLibs.

I wish more conferences were like UXLibs. There have already been posts written about what set it apart–the activity, the engagement, the integration of the keynote content *and speakers* with the agenda of the conference, the way the conference team did EVERYTHING including mentoring the teams and checking their luggage. Etc. It was a grass-roots conference, an activist conference, born of a conviction that hey, this ethnography/usability/qualitative stuff has legs, you guys, maybe we should talk about it and explore it for several days.

So, we did. My small part was to deliver the keynote on the first day, and run an ethnography workshop. My larger agenda was to witness the seeding of ethnographic perspectives among more than 100 people from libraries across North America, the UK, and Europe. It was fantastic. I saw the creation of what promises to be a hugely energetic community of practice. I look forward to what comes next.

In which I thank people, bear with me:

I need to thank Andy Priestner, Meg Westbury, and Georgina Cronin for asking me, in March of last year, to keynote. I need to thank the entire UXLibs team for including me in discussions of the conference agenda, and for their confidence that I was one of the right people to speak to their delegates. I need to thank Andy again, and Matt Borg right along side him for their clear vision and unwavering enthusiasm for this conference, and for my work as a part of it. I need to thank Georgina again for logistics and also enthusiasm. I need to thank Ange Fitzpatrick for unicorn menus and Cambridge Green. I need to thank Matt Reidsma for the best damn keynote talk I’ve ever attended. I need to thank Cambridge for being Hogwarts, really y’all, it was magical.

https://twitter.com/DonnaLanclos/status/577998947337273344

In which I say what I said in my UXLibs Keynote:

In my keynote (MY FIRST ONE YOU GUYS I AM STILL SO EXCITED ABOUT THAT) I wanted to set the tone by exploring what I thought was at stake in libraries and universities, and how ethnography and anthropology can restore/reclaim narratives generated by the practices and priorities of the people working and studying within our institutions.

That’s the TL;DR summary, btw. Quit now while you are ahead. You can read Ned Potter’s Storify of it instead, if you like.

The rest of this blogpost is an attempt to recreate what I said that day. I do tend to improvise and riff when talking (she said, unnecessarily), but I think this will give you the gist.

I wish to make the argument here for usability as a motive, ethnography as a practice, anthropology as a worldview.

Qualitative approaches provide opportunities, provide space, give chances for breath, reflections, possibility, and perhaps most importantly of all: persuasion.

I am going to talk for a bit about how i see those things, and then I want to hear from you. This is a conference centered on Practice. Let’s think about our practices together.

So.

Are you sitting comfortably?

Let’s begin.

Libraries are artifacts

Little Free Library Easthampton photo by John Phelan: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Little_Free_Library,_Easthampton_MA.jpg

Universities are artifacts

They are made things, they emerge from particular historical moments and social processes embedded in the lives of people.

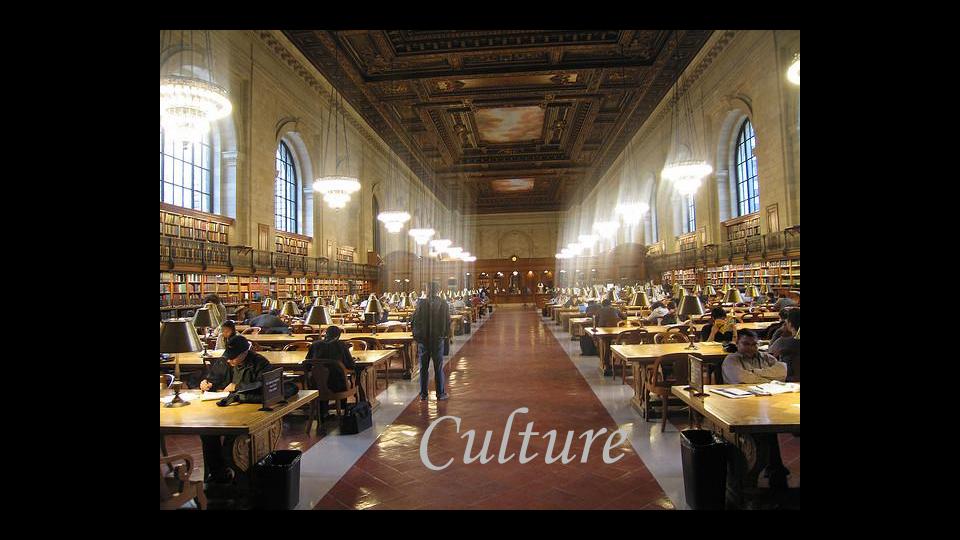

Libraries are cultures.

NYPL photo by Ran Yaniv Hartstein: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NYPL.jpg

Universities are cultures.

There are conventions of behavior and expectations that come along with being in a library, being in a university, there are roles and structures and rules, subcultures and communities.

Libraries are places

Photo of UNC Charlotte Atkins Library ATRIUM by Donna Lanclos

Universities are places

Places are also cultural constructions; these are the layered meanings that are put over spaces by the people who inhabit, move through, and even avoid them. The identity of the people within these spaces informs what sort of place they become.

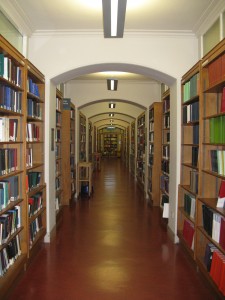

Once upon a time, Libraries were measured in terms of how large and rich and unique their collections were. The great collections were those that attracted scholars away from their home institutions, the great institutions were those capable of amassing enough in their collections to keep their scholars at “home”—the goal was to make it so their faculty would not have to leave the university to do their academic work.

Of course very few (if any) achieved that goal, but the tight circulation of scholars among the great collections of libraries such as the British Library, the Beinecke, and so on reveals the network of traditionally rich scholarly institutions, traditionally great libraries, with richness that was quantifiable and easily measurable.

But we cannot all rest on the laurels of our marvelous historic collections. Each library has the potential to be both less and so much more than the great traditional repositories.

Libraries are portals today, as they have always been, to content, to information. They are increasingly locations — both digital and physical– that provide not just access to content (text, videos, documents, artifacts, datasets), but to a place where people can also produce something new. As locations for creation libraries stake a claim to something new, and something terrifically difficult to quantify. What do we talk about when we talk about the value of libraries? Do we need to quantify what is valuable? What are the things that make up libraries and universities? What are the different ways we can describe and advocate for them?

What happens to the story of libraries when we who work in them take the risk of de-centering our expertise, allowing space for students and faculty and other inhabitants of our spaces to speak to what libraries mean for them, independent of our intentions?

What happens when we (like Andrew Asher has done) approach Google not as a competitor, but as a made thing, a piece of cultural process?

What can we learn about searching for information once we look outside of the library?

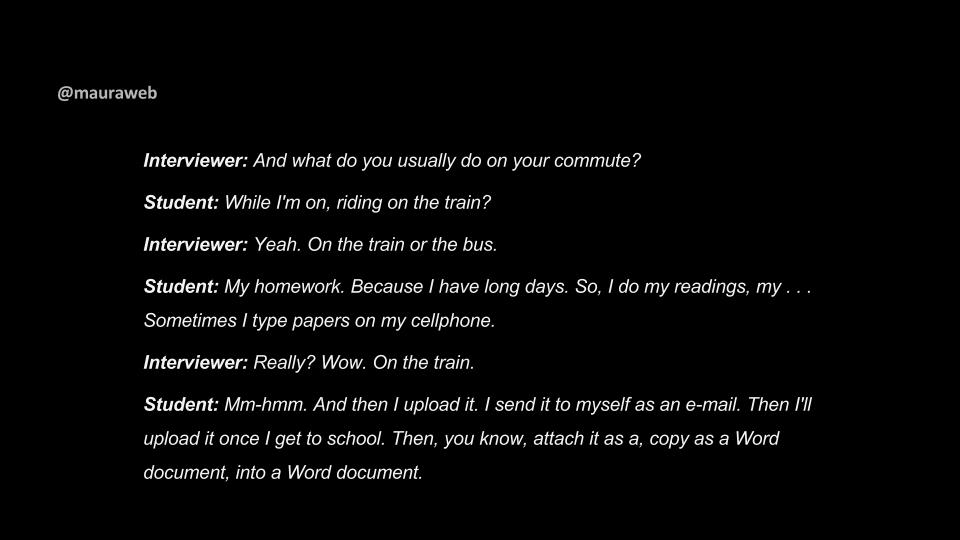

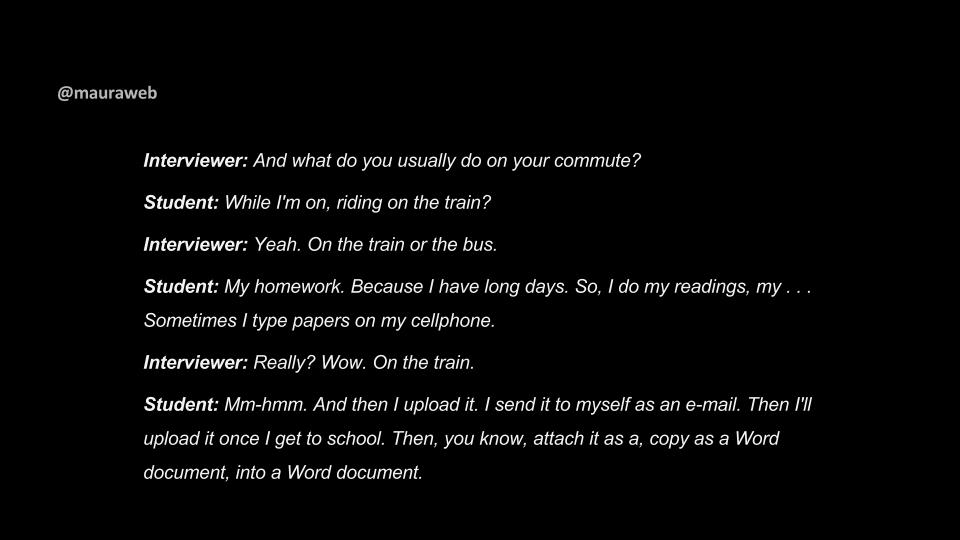

What happens when we, as Maura Smale and Mariana Regalado do , demonstrate that students are writing research papers on NYC subway cars, using their phones?

What does that teach us about the nature of research and writing outside of traditional academic places?

What happens when we take on other people’s definitions of academic places?

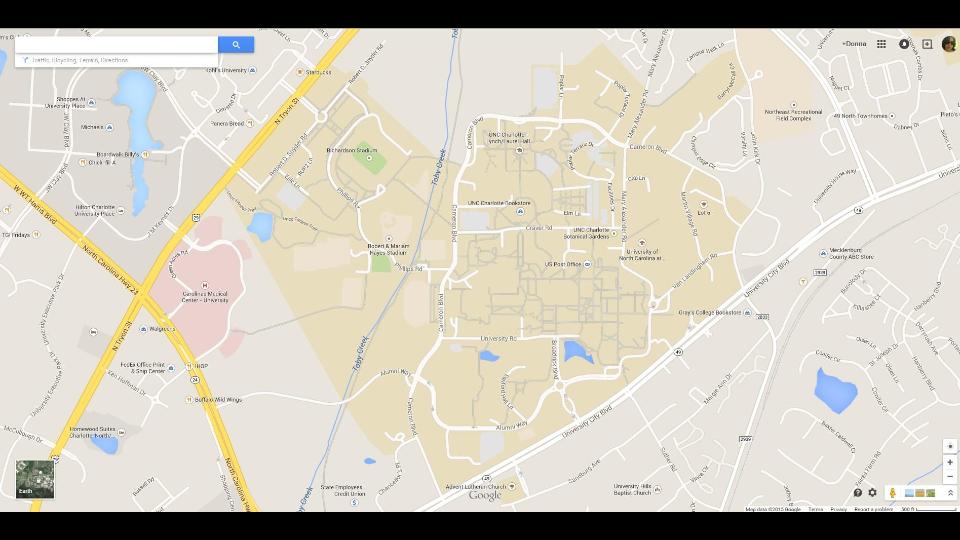

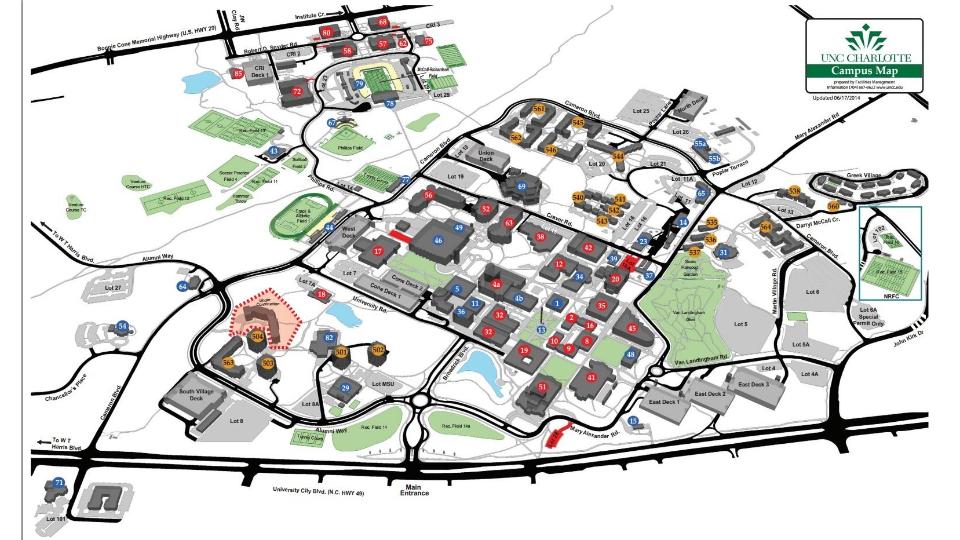

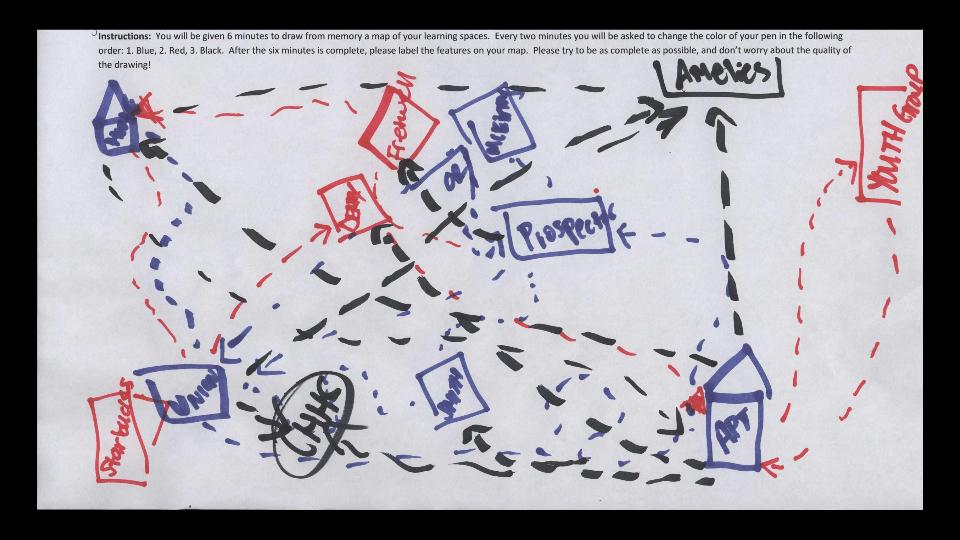

Think about the difference between this picture of a university

http://masterplan.uncc.edu/sites/masterplan.uncc.edu/files/media/final_aerial_v2web_2.jpg

the map that Google gives us

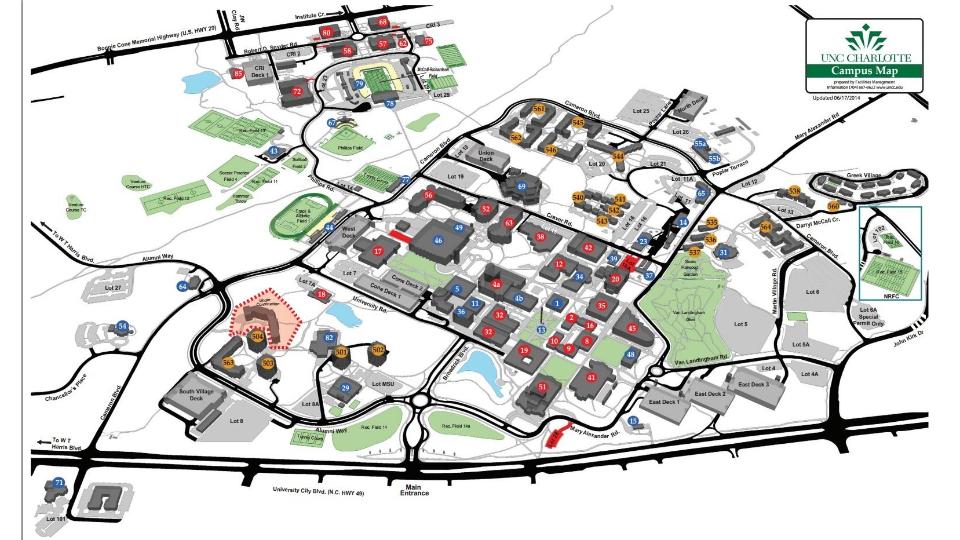

the map the Institution provides

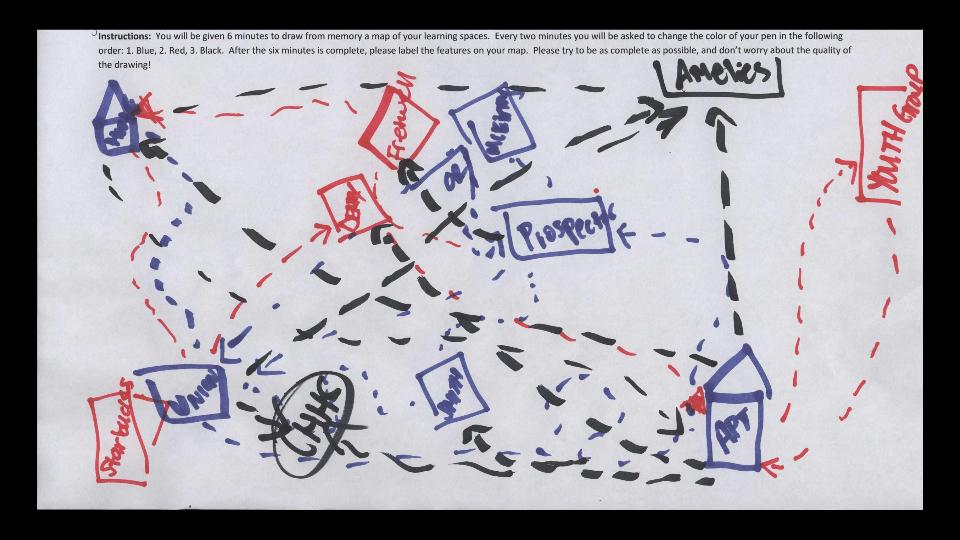

And this.

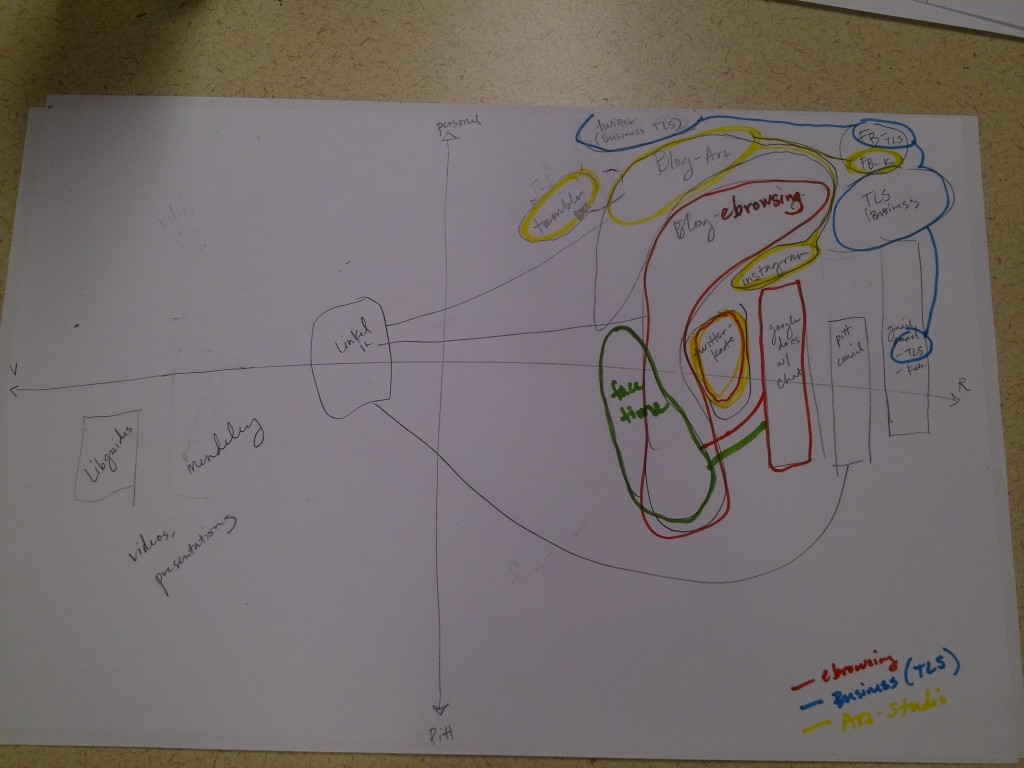

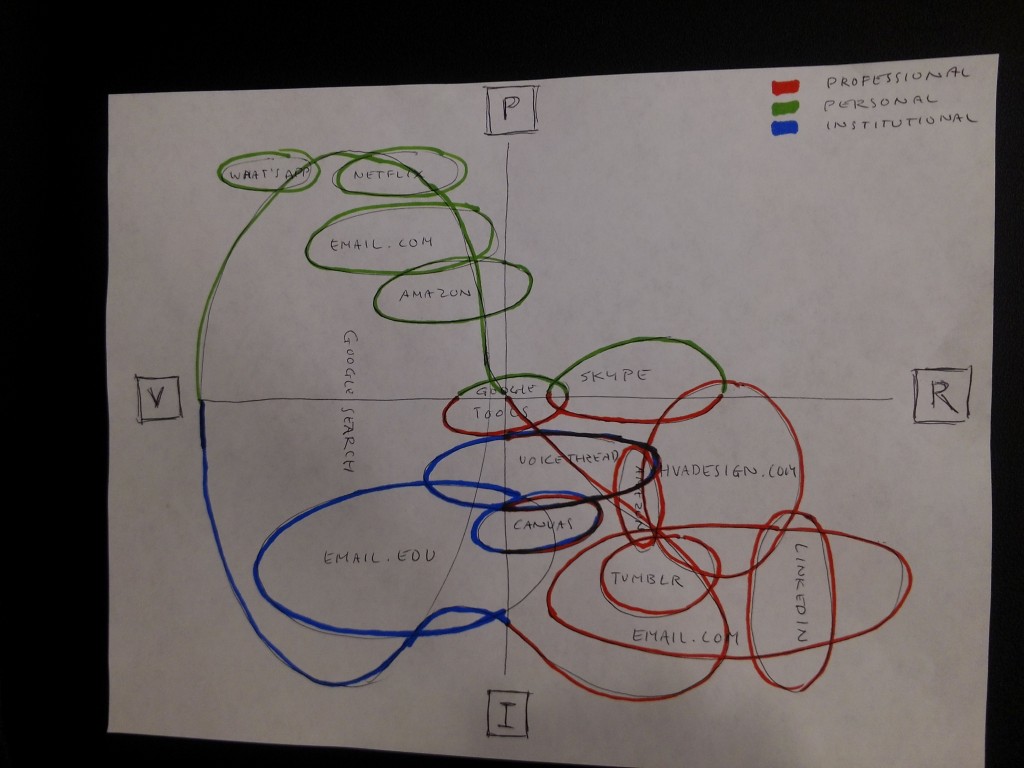

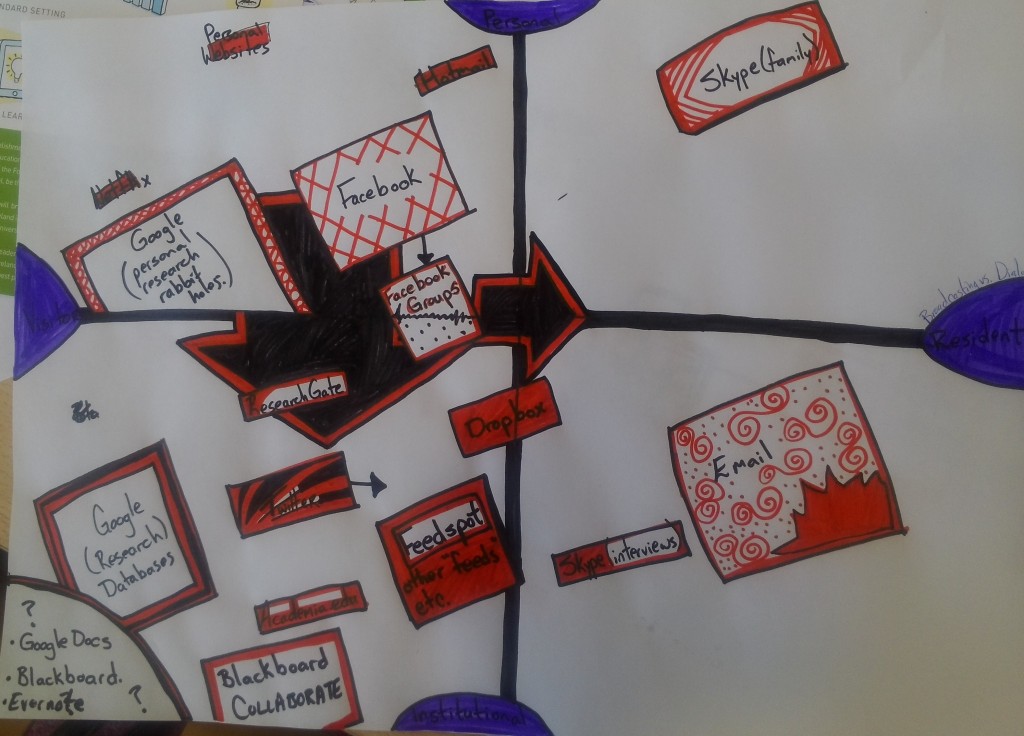

This map of a UNC Charlotte student’s learning places shows all the things we don’t see if we limit ourselves to institutional spaces. This map is a story, the meaning of this person’s life is shot through the lines of activity, the calling out of institutional and non-institutional space, the people who she encounters or avoids in the living of this map.

Maps like this tell stories, show us that the library does not exist in isolation. Perceptions of importance, accessibility, of usability do not originate with the library, but in the non-library spaces that people are familiar with. Higher education generally exists in a larger cultural context—what makes it navigable or incomprehensible is that larger context. Connecting what we do within libraries with the expectations of the people who come to us is crucial—this is not the same “giving them what they want,” or “dumbing things down.” It is working to mindfully translate the value of what we have using recognizable signals from non-academic, non-library contexts.

Because what do we want to spend our time doing? Showing people maps of our corridors? Demonstrating how to click links on our website? Or, do we want to streamline access to information and resources so that people can engage in the heady work of making? And we can join them.

That sounds amazing to me.

How can we do that work, in the current institutional culture of assessment?

Just as academic departments with responsibilities for instruction do, libraries– as institutions within higher education– have to confront Assessment

Jesse Stommel (one of my favorite people on Twitter, and a writer about pedagogy) asks the important question:

“Does this activity need to be assessed? Or does the activity have intrinsic value? We should never assess merely for the sake of assessing.”

National Survey of Student Engagement is GOING TO EAT YOU. Image by Maggie Ngo, UNC Charlotte Atkins Library.

The monsters of assessment.

And here I am inspired by @audreywatters discussion about technology. We have fed this monster, too, in our quest to Prove the Value of Libraries, we have taken it as written–far too often– that speaking in numbers is effective speech, that the way to demonstrate value is to count and quantify.

These monsters plague institutions, because there are some things that assessment wants us to do with numbers things that we simply cannot do.

Particularly with regard to learning.

We can describe, demonstrate learning. But measure? What does testing measure? What is the measure of an education? Where do we see the results of education? I am not talking here about content knowledge, I am talking about fluencies of thinking, of questioning, of connecting, of creating. Where can we see that in action?

In practice.

In places like these.

Scenes from students working at UNC Charlotte’s Atkins Library, UCL’s Student Union, and UCL’s Institute of Archaeology library. Photos by Donna Lanclos

How does one measure practice?

One does not.

In the course of my work, I want to dispense with the idea that the important things in education are measurable, and turn instead of qualitative approaches to inform our thinking about teaching, learning and education.

I want to allow for pause, for insight, for reflection, for description and analysis of meaning and behavior. I want to reveal the relationships that impact the decisions that individuals make, that reveal the consequences of those decisions. Not in terms of “success” or “failure” according to metrics, but according to the narrative of people’s lives, the revealed landscape of where they work and live and interact with people, and why.

UX is a motive

Why do we care about usability?

I think institutions can care about usability in the service of selling more things to more people. They can care about the behavioral logic of their “customers” so that there is increasing levels of satisfaction with what is bought or consumed, and also a loyalty to institutions who provide good experiences or “good value”.

That is the marketing approach. That is a relatively mercenary way of drawing attention. “Try us, you’ll like it, we’re easy.”

But we are in Higher Education. We are in public service. We are libraries, we are universities, we are educators, resources for people who need more than information. We are for people who need to use information effectively, who need to think critically about information, who need us as partners in navigating the information landscape, and who can also become people contributing to the layout of that same landscape.

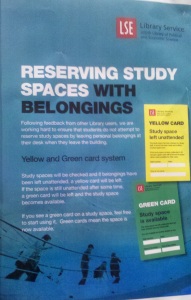

And this is where usability as a motive is very very important. It’s another way of talking about Access

If our systems are so complicated, our buildings so illegible, that they require mediation, that people walking into our libraries or encountering our web environments for the first time have to come to us for help in navigating links, or hallways, we are wasting everyone’s time. We are spending time being a tour guide, a traffic cop, a gatekeeper when we could instead be having conversations, picking things apart, writing things, analyzing thoughts, making something new. We should aspire to be doing so much more interesting things. And we have a responsibility to be accessible.

Because the purpose of education is not to produce people to work at jobs. It is to produce effective citizens. Engaged human beings. People not just capable of independent thought but people who revel in it, who are so good at it that they come up with solutions to problems, that we make the world around us a more engaging, more constructive, more supportive, yes, a better place.

If the only people who can comprehend what we are doing are the people who already know the secret passwords, who already have the map, the keys to the kingdom, we have failed.

Then we are not educating, we are sorting.

Critical thinking happens in groups—distributed cognition about value and authority happens all around us. It’s particularly visible on the web in the form of reviews, but also in blog conversations about theory, in twitter discussions of policy, in Facebook fights about inappropriate jokes and memes. Libraries and universities provide nodes where people can come together to think, to argue, to consume with an eye to produce. UX can help us think about the kind of environments that are short-cuts to that production. We have the chance to think about physical and digital places that don’t get in the way, but that accelerate the process of scholarship, of communication, of effective policy, of education.

Libraries are made of people

Soylent Green poster by Tim (tjdewey): https://www.flickr.com/photos/tjdewey/5197320220/

Universities are made of people

I think here again of the work of Jesse Stommel and also Dave Cormier talking about curriculum and courses. They each make the point that community, the people in the course, are the content of that course. “Intensely and necessarily social” is the phrase Jesse uses.

It echoes nicely a point Lorcan Dempsey made a while ago, “Community is the new content” of libraries–we are not about collections (as if we ever were), we are about relationships, people and what they know and do and produce are part of what the library facilitates.

Libraries made of people, and the work of those people:

How then do we study people?

Ethnography.

Ethnography is a practice

There is a range of methods within that practice, I won’t rehearse them here. I want to pay attention to the part of the story that talks about what the results of engaging with those practices can be.

I understand the skeptics of ethnography in design. All that work, and what gets done with it? To what extent are ethnographic studies being used to justify what is already suspected to be the case?

How can we who work in institutions be more than automatic approvers of institutional agendas?

By being part of the full time team. And by being more than methodologists. It’s not just about the methods, it’s about what happens when you do this work, and with whom you work.

I’ve spoken about this before—we practitioners of ethnography are far more useful to you if we are around all the time (we may also be exhausting that way). When we are brought in as consultants we have customers, and some pressure to please, however much we value our potential role as provocateurs. When we are hired full-time, we are colleagues, and our awkward questions, our explorations of issues and patterns that are not immediately related to problems at hand, are in service of the greater good. When we are invested in the organization, we want our work to contribute long-term, we have the time, the bandwidth, the organizational support for trying and failing and occasionally going into dark corners that people don’t habitually visit.

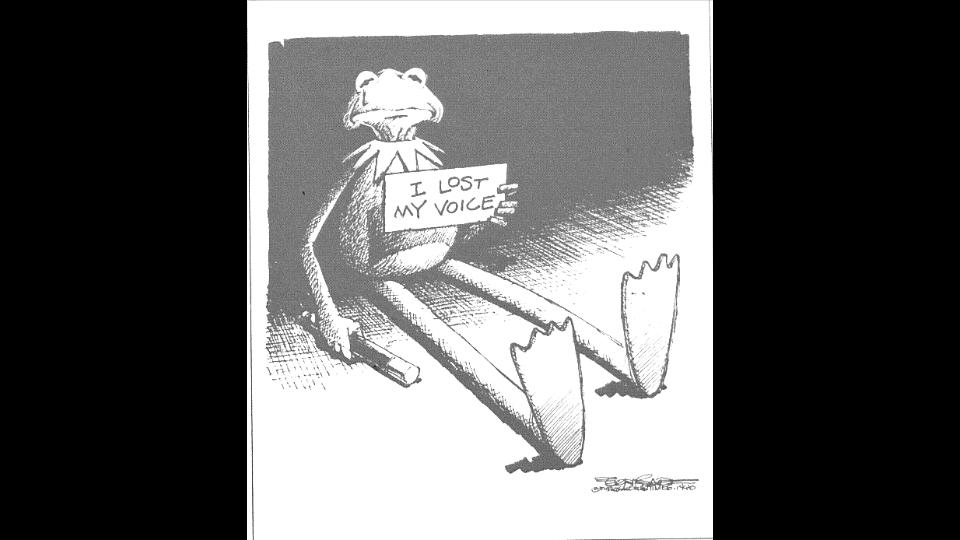

Libraries have voices.

Kermit lost his voice: Conrad, P. (1990, May 20). Editorial Cartoon. Los Angeles Times.

Libraries have lost their voice.

Look at what happened in December at Barnard College–their university librarian left, library perspectives were left out of the conversation about the new “library.” I look at things being built or imagined on a variety of university campuses and think, “Well, that looks like a library to me!” But some of the new things aren’t even called libraries–they are called “Hubs”, I have seen “learning centers” and “Commons.”

We need to keep “Library.” It is a word that has associations that some people think should be left behind, but part of the power of the word “library” is that is can mean so much. Books. Quiet. Shelves. Distraction. Friends. Computers. Space. WiFi. Librarians. Refuge. Anxiety. Cafe. Printing. Scholarship. Community.

With a voice, libraries can shape perceptions of themselves. Engaging in ethnographic practices can be one way of building and exercising that voice.

Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte. Photos by Donna Lanclos and Cheryl Landsford, UNC Charlotte.

For example, on the ground floor of Atkins library (where I work)–data on student behavior gathered via ethnographic methods gave us the information we needed to tell effective stories to administrators about the kinds of spaces we needed to configure for our students [slide of the new ground floor]. Our attention to UX and ethnography has made us, at this point 5 years after we started with agendas, an authoritative voice in our university around physical and digital policies. The library is not just in the library anymore. Engagement with these methods have given us a voice that is heard, a place at the table.

Once you invite these practices into the the everyday way of doing things, it can be institutionally transformative. It takes time. It is inexact at times. It requires reflection, the backing away from assumptions, it involves being uncomfortable with what is revealed. Institutions willing to take on those complications can thrive—eg where I work. Eg here at Cambridge. Institutions who want the publicity that comes from ethnography but not the work, not the ambiguity, and not the full-time commitment, will fall short. They will miss the opportunity, will fail to find new ways of talking to the people who hold the purse strings about how and why to spend money, resources, time, effectively, in our larger project of education.

Think of the act of ethnographic description, the moment of insight, as a simultaneous act of deconstruction. It is not simply a bundle of methods, (Dourish and Bell location 904 Kindle edition), but theory, a way of seeing, and analysis.

Anthropology is a Worldview

We need more than methods and practices, we need anthropologists

We need ethnographic practices, informed by anthropological perspectives.

We need to ask questions, to find things out. It is not enough to observe, we have to ask.

Asking questions is a good way of finding things out, Big Bird taught me that in my childhood.

What do I mean by a pedagogy of questions? It’s teaching through asking. Not by telling.

I want to pause the discussion of libraries here and talk about a question that I heard in 1997

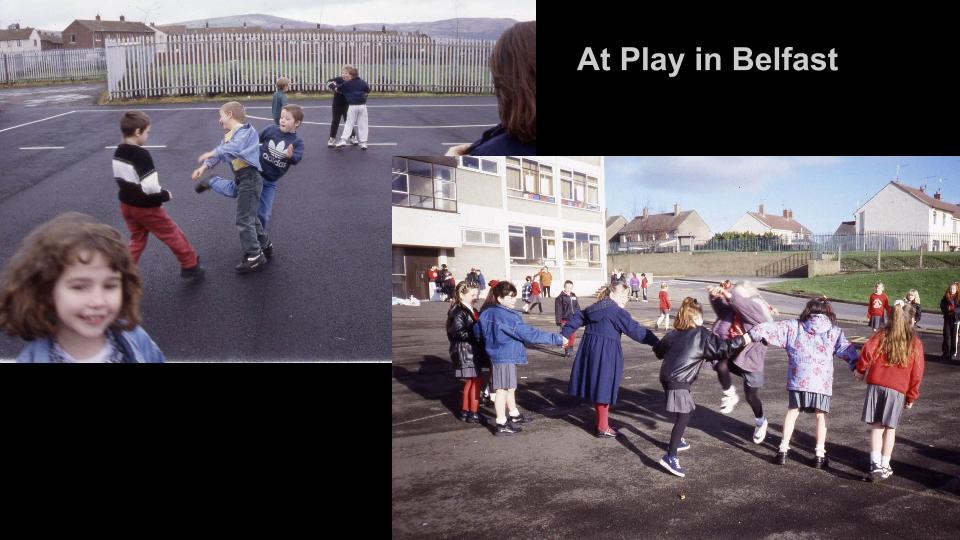

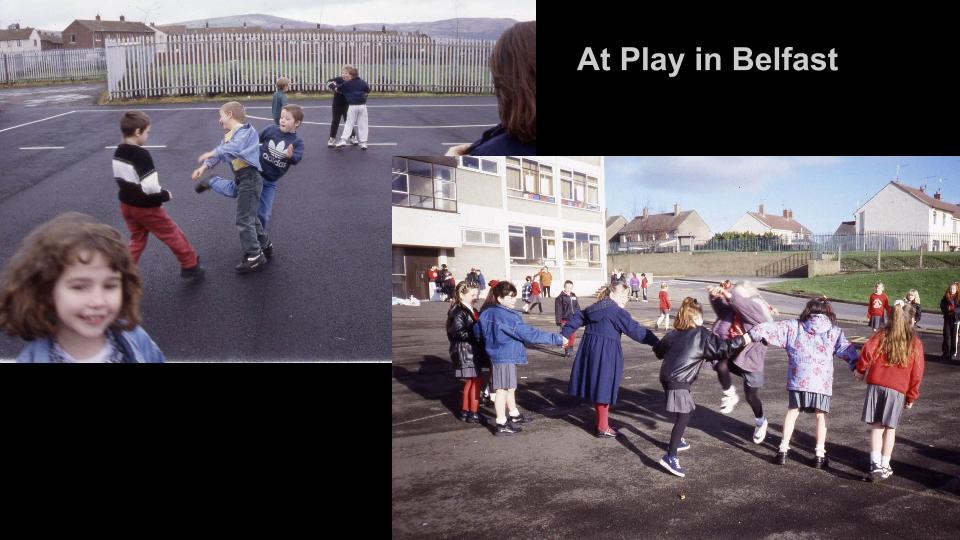

Photos by Donna Lanclos

My Belfast fieldwork was among primary school children, I was doing cross-community work, collecting their folklore in playground settings. I will ask you the question now:

[note: I said the question aloud in my best attempt at a Belfast accent]

Can you understand that? What does it mean?

What is it asking?

How can you know?

This question was asked of my husband, not of me, because he was new to my field site (arrived 4 months after I did)–the kids assumed I knew already, and assumed he needed to know.

This question is actually an act of teaching. Understanding this “catch” question requires knowledge beforehand. You have to know something about Northern Ireland, its divided society, before you can start to put the pieces together, so that we know that the Pig = P = Protestant, and Cow = C= Catholic. Whether you answer “Pig” or “Cow” depends on who is asking the question. Do you tell the truth? Do you need to “pass?” Can you tell the identity of who is asking so you can suss out the “right” answer?

Why do people want to know these categories? Because they live in a divided society, and identities and allegiances matter. Kids were teaching each other, through this question, what sorts of questions they needed to ask, and also what they needed to know before they started asking questions at all.

You have to know something about the situation on the ground before you start asking good questions, ones that will get you somewhere, to a greater understanding.

An anthropological perspective is one that generates questions.

Anthropological perspective comes from a place of agnosticism, from what @jessifer calls “a voracious not-knowing.”

We position ourselves with no answers. We end up usually finding simply more questions. There is a power in that. An anthropological perspective, seeing with an anthropological eye, requires deliberately positioning yourself as the person in the room who knows the least about what is going on. That is hard, not the least because we are professionals with expertise and we JUST WANT TO SHARE IT WITH YOU so you can DO THINGS RIGHT.

Think for a minute about the position of libraries in higher education, and about who listens to libraries. In general it’s: other libraries. Finding a voice in higher education, and people outside of libraries who will listen to us, depends in part on our generating interesting questions. This is far more useful than telling people what they should do This is not to say we cannot come up with answers to some of the questions–but many of the answers we uncover are problems. And it is in our accurate identification of problems that we can be truly useful. When people think that one sort of thing is “wrong” their perceptions of why that situation has come to pass can be incomplete, or completely off-base. When some of the answers we provide are the outlines of Problems then we are truly worth listening to.

So we are not talking here just about a pedagogy of questions, but an ontology of questions–queries nested within other queries, things we do not know influenced by what we never found out.

Image by Maggie Ngo, UNC Charlotte Atkins Library.

Questions such as:

What are people doing when they talk about “intuitive” design? Intuitive for whom? What constitutes “intuitive? Who defines it? What is that experience, of feeling something “intuitive?”

What is studying? Is it the same as “learning?” Who is in charge? Is that a meaningful question? What are the power structures we can reveal by tracing the actions and reactions of students, faculty, and staff in academic spaces? What is made, what is observable? What can we see, what needs more work before it can be shown?

You have to decide when to stop asking, start trying to work towards answers (and be OK with coming up with more questions).

You have to be capable of picking the moment where you stop questioning, if only for a bit. And also recognize that the place you have chosen to stop is relatively arbitrary–but it should be a useful place.

And for it to be useful, you should be embedded enough to know enough to be able to interpret the meaning of questions, and deploy them effectively. You have to know stuff; questions cannot be asked from a position of absolute ignorance. You have to keep watching, to observe. You have to ask questions of lots of people and then interpret what they say, in the context of all of the other information you have gathered.

I would say that I’m going to stop asking questions, because I know it’s annoying but you know what? Being annoying can have its perks, too. Being annoying, making people uncomfortable in their assumptions, that’s part of my job. That is part of the purpose of engaging in this kind of work.

Upending, challenging, questioning.

Observations are not the same thing as insight

Answers are not the same thing as solutions.

Our job is NOT to find answers. It is to provoke questions.

And the joy of it all is that we, for all the questions we come up with, we do not have to come up with Solutions.

That is the other part of what is at stake. Once people are listening to us, we can engage them as part of the solution, or even a range of solutions. We no longer, in this scenario, have to be subjected to solutions imposed on us from without. We can generate solutions as a team, with our colleagues in HE.

Anthropology– Indiana Jones notwithstanding– is a team sport when done well. Particularly in the case of applied, practical work. Library ethnography, and UX work generally can be usefully thought of as multi-sited ethnography: different locations, but connected systems with connected problems, connected cultural phenomena across higher education, across society, across whichever plane in which libraries and universities exist.

I want to emphasize the importance of sharing, of collective thinking, of not thinking of ourselves as special snowflakes, of not allowing the tendency to silo distract us from what we can reveal, confront, solve together, as a team. So, when one person sees a library as a system, and the other sees it as an artifact, then there is a need to translate, to recalibrate , so that a conversation, an engagement can happen, and we do not end up just talking past one another.

UX, ethnographic practices, anthropological insights should all be just the start of a much larger agenda in libraries and higher education. Making systems and spaces navigable and legible is important if we take our mission of access seriously. Understanding why something is navigable or illegible in the first place takes a deeper understanding, and can lead to insights beyond design, to organization, culture, process.

The act of ethnography, the interpretive lenses that anthropology can inspire, can help us fight agendas that are destructive to that educational project—being deeply embedded in the behaviors, in the lives, of our students, our faculty, can give the lie to the vocational narrative of neoliberal educational policy. The people who make up our institutions are more than a list of certifications, more than the money they might make, far more than the boxes they tick off as they work through their course modules in pursuit of their major. Those people are revealed with qualitative research. Their stories move policy makers. We do not have to take policy-makers’ word for it. We do not have to take the web template lying down. We do not have to believe them when they tell us that students no longer read, or will only communicate via text, or have lost the ability to think critically. We can push back, and point out the explosion of different kinds of reading, of all the different places where communication happens, that it’s our responsibility to model and teach critical thinking, not just assume that it will show up as they arrive to campus. We can leverage our grounded sense of the lives and priorities of people to make effective arguments, to drive our own agenda.

To tell the stories we see around us. To tell our own stories.

Thank You. (for reading, for listening)

Thank you to those who, whether they knew it or not, helped me think of what to say. Follow them on Twitter, read their stuff wherever you can find it.

@audreywatters @davecormier @lorcanD

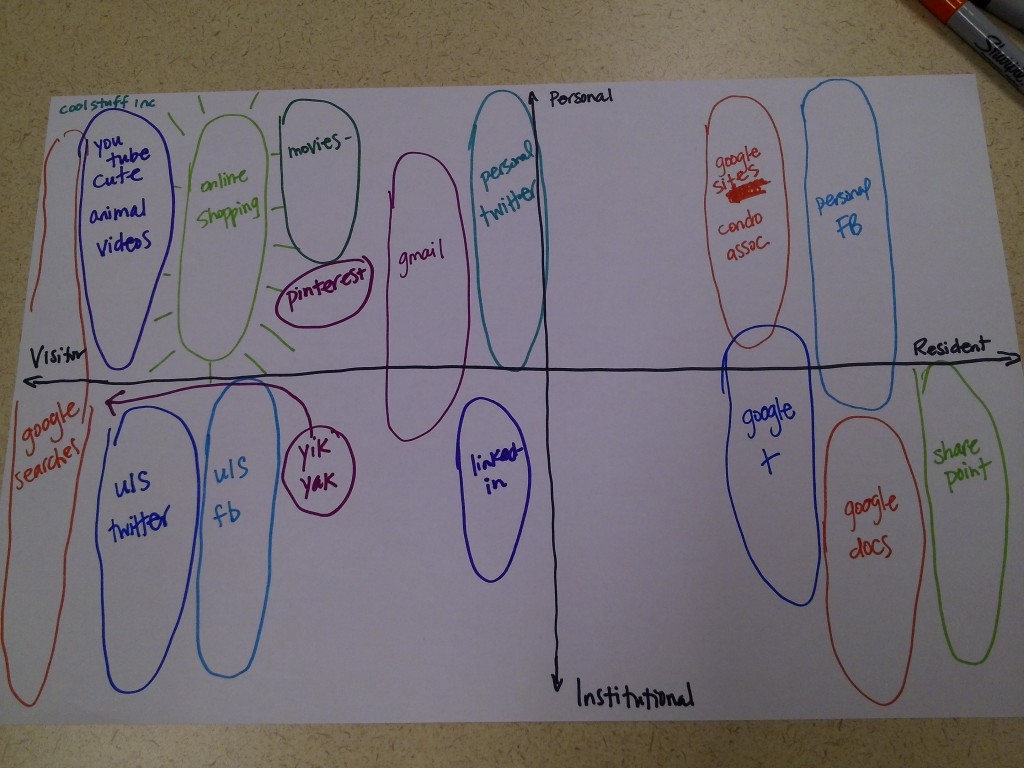

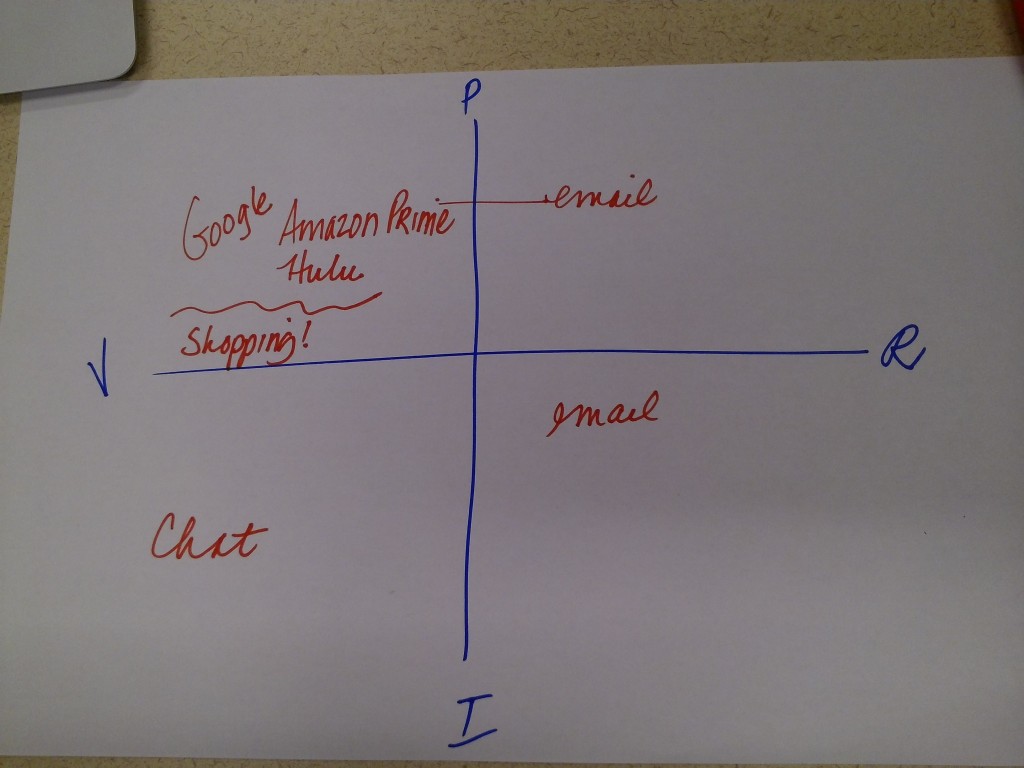

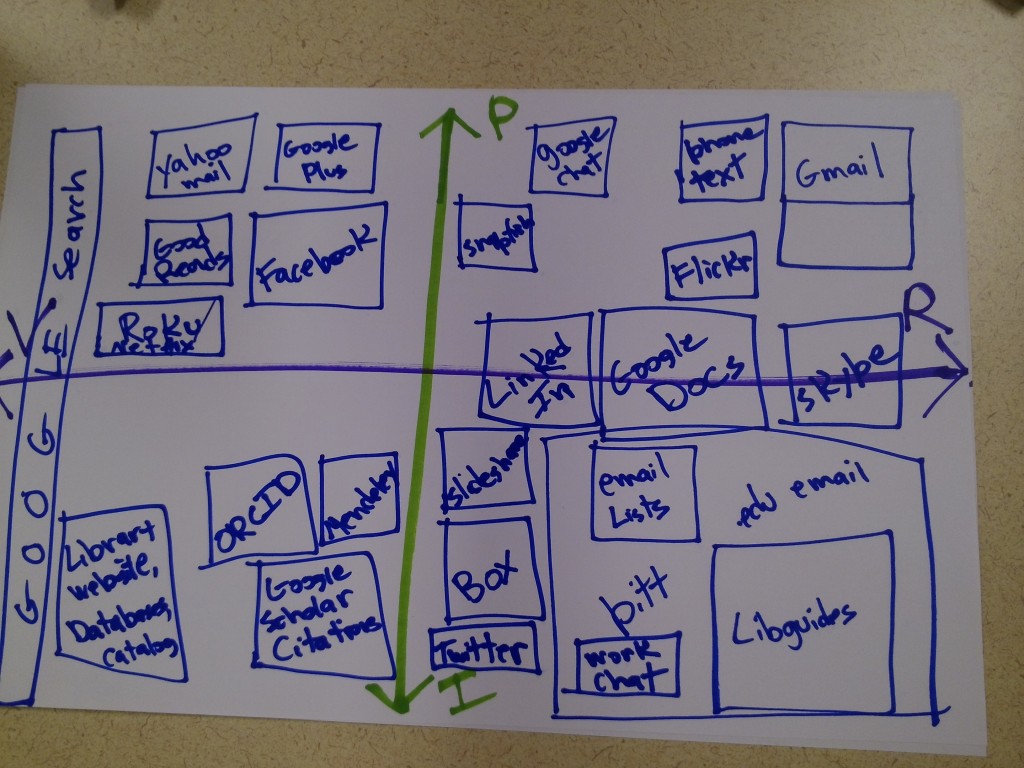

@jessifer @daveowhite @aasher @librarygirlknit

@mauraweb @PriestLib @mattjborg