I was at ALA to help conduct participatory design sessions on behalf of the Visitors and Residents Project. We are at the point in our long-term project that we’re conducting expert sessions on modes of engagement with technology and information, where we’d like to produce resources that can help others think about and configure the things they are doing with a focus on what their patrons/users/constituencies need and want to do.

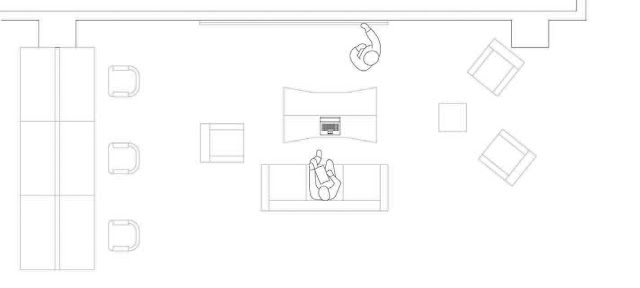

V and R map of a library professional, showing lots

of Visitor mode and Institutional contexts (in these maps, the P-I axis is

Personal/Institutional)

To that end, we (where “we” = Lynn Sillipigni Connaway and Erin Hood from OCLC, David White, and myself) convened 2 different sessions with library experts–leaders in their fields, in their libraries, in their departments. We asked them to map themselves on the Visitors and Residents polechart that we’ve developed and have been using with librarians and educators (in the US and the UK) to discuss how individuals get information and engage with technology for their personal and professional/academic needs.

We then asked the participants to map their constituents.

|

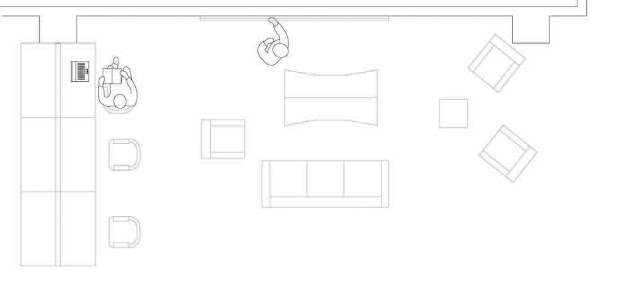

The same professional who produced the above map chose to map their perception

of Undergraduate engagement, with heavy emphasis on Resident-mode and Personal context. |

And then we talked.

There was a lot of talk, and it was fantastic and constructive. So now, we’ve got a great deal to process. I have blogged before about where things like Facebook show up on V&R maps, and I have the persistent sense that what tool/digital space people are using/inhabiting is less important than what they are doing in that space/with that tool. That is, as Dave pointed out during the session, it’s not enough to count how many students are on Twitter, or FB, or whatever. You have to do the qualitative work that tells you just what they are doing in these environments. Some use FB to connect with people, but some connect with people only via direct messages, others post everything to their wall. Some use FB as a clearinghouse for all of the events and organizations they want to track. And so on. Our analysis of what people are doing to engage with resources should ideally be tool-agnostic. It is the same way that IT support should be device-agnostic; you should be able to do your work whether you walk into academic spaces carrying a Mac or a PC, a netbook or a phone, etc.

So, a media strategy that identifies FB as important, but fails to grasp the details of why, is not going to be a terribly successful one.

One of the other things I’m processing is something we’ve been talking about amongst ourselves in the V&R group for a while, because it’s coming out of our data loud and clear.

This will surprise very few of you, I think: There is a difference between Participating in Academia, and Learning.

Our interviewees reflect the tension between learning and academic practices every time some of the participants apologetically talk about how they use Wikipedia as a starting point to get themselves ready to dig deeper (or not) for the work they are doing. Lower division undergraduates describe a process familiar to many a college instructor when they talk about constructing an argument for their essay first, and then going in to do quick searches so they can insert relevant references. They are producing something for the academic process, but are not necessarily learning.

We do see them talking about learning, when they are engaged with the material, or with the person teaching the material, or if there is so much at stake for them to learn it that they do it even if they are not really interested.

This disconnect makes me think of the reading I’ve been doing in the Community of Practice literature, especially the work of Wenger and Lave and Rogoff (cites below). My take away from reading this literature is that C of P theory is a really nice way of framing what happens when people learn how to be members of groups. The literature describes a wide variety of groups, including vocational, educational, and recovery. Central to Lave and Wenger’s 1991 discussion of Cs of P is the idea of Legitimate Peripheral Participation. I’m going to quote here:

“We intend for the concept to be taken as a whole. Each of the aspects is indispensable in defining the others and cannot be considered in isolation…Thus, in the terms proposed here there may very well be no such thing as an ‘illegitimate peripheral participant.’ The form that the legitimacy of participation takes is a defining characteristic of ways of belonging, and is therefore not only a crucial condition for learning, but a constitutive element of its content. Similarly, with regard to ‘peripherality’ there may well be no such simple thing as ‘central participation’ in a community of practice. Peripherality suggests that there are multiple, varied, more- or less- engaged and -inclusive ways of being located in the fields of participation defined by a community. Peripheral participation is about being located in the social world. Changing locations and perspectives are part of actors’ learning trajectories, developing identities, and forms of membership (35-36).”

They further make the point that legitimate peripheral participation occurs within social structures, involving relations of power. So, different power relations can serve as barriers to participation, or facilitate it. There is no inevitable progress towards a “center” in this structure, but an attempt to give theoretical structure to a malleable manifestation in society.

They emphasize that it is not “itself an educational form, much less a pedagogical strategy or a teaching technique. It is an analytical viewpoint on learning, a way of understanding learning. (40)”

I find it tremendously useful to have this in my head when I am thinking about the interview data we are collecting in the V&R project. The practices they engage in are acquired in social matrices of friends, family, peers, teachers, co-workers, and supervisors. The relationship our research participants have with the people from whom they learn practices, in turn, informs the relationship they have to the practices they acquire, the resources they choose to consult, or reject.

The confidence they have in the practices they acquire appears to be directly related to how connected they feel to the community they are participating in. And that has less to do with abstract notions of best practices than it does with the familiar (not to be confused with convenient, although that comes into it as well), that which is engaged in by people whom they trust, with whom they already have relationships.

So, if we in libraries want to transform the ways that people are engaging in academic work, or at least, actively participate in the changes that are happening around us, we need to be fully embedded as community members. Students will come to us and work with us when they recognize us as part of their network. As faculty members, and/or people who work with faculty members, we in the library need not just to engage in the practices of academia, but advertise widely that we are engaged in such work, so that we are visible members of the community. And when we recognize barriers to that participation, we need to work collectively to overcome them–such problems cannot be solved by individuals.

The beauty of the Legitimate Peripheral Participation idea is that there is no one “right” way to do any of this. There are potentially many effective ways.

We also need to think about which community we are preparing our students to participate in as members. Are we preparing them to be Academics? Is that the best overall approach? Or should we think about what to do to prepare an informed citizenry? I really appreciate Barbara Fister’s blogpost from today on this last point. Our responsibility, in libraries and in education generally, is not, I think, to merely reproduce another generation of academics, but to send people out into the world better equipped than they were before for participating in civil society.

******************************

References

Lave, Jean, & Wenger, Etienne. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive, and Computational Perspectives. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Rogoff, Barbara. (1990). Apprenticeship in Thinking: Cognitive Development in Social Context. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wenger, Etienne. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive, and Computational Perspectives. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

[with thanks to Lynn S. Connaway for editing suggestions, and Erin Hood for the V&R scans, and Dave White for saying things that I wanted to write down in this blogpost]