Those of you familiar with me on Twitter know that I’ve got frequent rants against Digital Natives in my feed, and I’ve been indulging in such rants more often lately, as there’s been a rash of people on the internet and in person invoking that particular trope.

I’m not going to spend time here debunking the Digital Natives thing, I’ve done actual work that helps deconstruct it, and that offers an alternative.

I think (it should be clear) that it’s important to stop thinking in terms of Digital Natives, and to stop giving an eye-rolley pass to people who do. I’m writing this at least in part to have something to link to when I don’t want to write any new rants about this. It’s not just that the Digital Natives thing is wrong, it’s about what is at stake if we continue to allow it to ease its way into conversations about pedagogy and technology. Alternatives, whether Visitors and Residents or otherwise (though I’m fond of the former), are just a more ethical way to go.

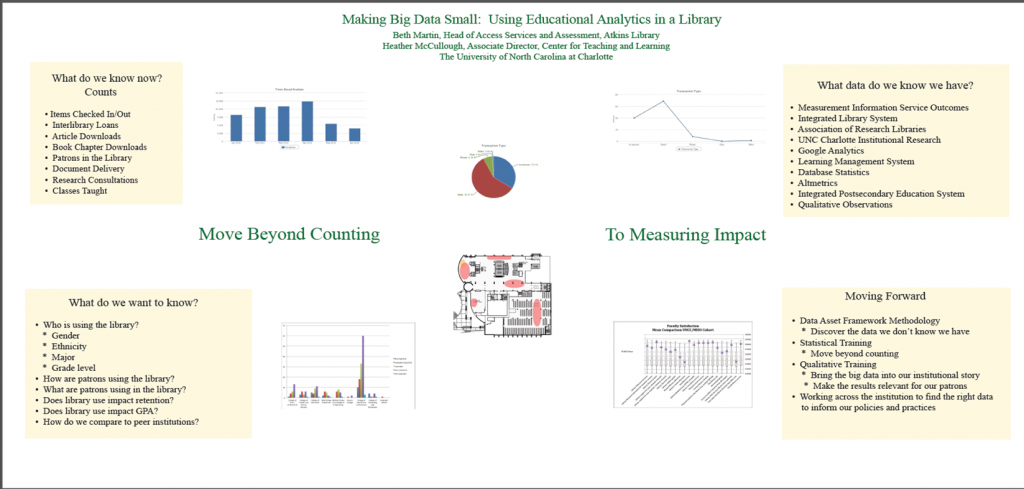

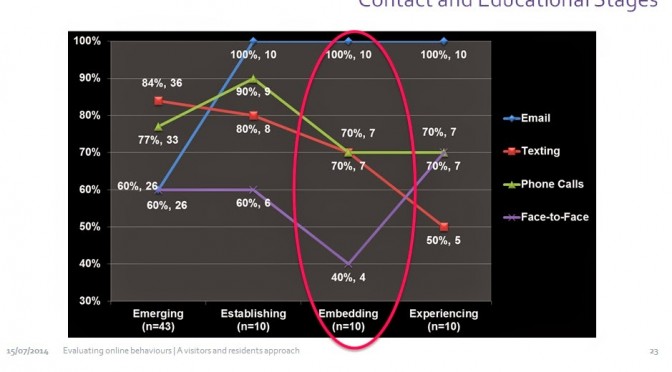

First of all, the Digital Natives construction assumes that you know 1) that people of a certain age are engaged with technology, and 2) that you know why. All that is left to do, under that model, is count how many people have what kind of tech. Framings such as V&R insist on engagement with the qualitative data, with the complex behaviors of people, so that we can understand what is going on, not sidestep understanding via quantification.

Second, the cliche, lazy generational generalizing that Digital Natives indulges in is an imagining of a seamless present, wherein the mere presence of technology results in expertise that is untaught, in fact fundamentally unteachable, and therefore pre-existing, and something to expect from students of a Certain Age. This is more dangerous than the seamless future that so many of us imagine (of education, of libraries, of ubiquitous computing–I’ve been reading Dourish and Bell’s Divining a Digital Future and am clearly influenced by it here). Future thinking is unfortunate because in part it encourages a neglect of the complicated and messy (and interesting!) present. It’s easier to think and talk about a future where the current problems with which we wrestle are fixed (jet packs!).

It’s far more challenging to confront the present.

And the present being confronted should be a finely and accurately observed and described one, not an imagined present. Digital Natives hands us an imagined present wherein Kids These Days Can Just Do Technology. It is a tailor-made justification to neglect a responsibility to the people we need to teach. The cliche suggests that we can ignore the messy complicated present where the ubiquity of computers still does not automatically (automagically, to steal from @audreywatters) produce any sort of literacy or critical thinking. We have a situation right here in front of us where engagement with technology is not pre-determined by age, but by a complex interaction of identity, economic class, privilege, power, and a host of other factors that enable or restrict people. Let’s talk about that, not about how young people Get It and older people Don’t.

I think as a construction, given all we know about the whys and hows of people’s motivations to engage (or not) with technology and information, Digital Natives is thoroughly reprehensible. It’s not borne out in the research, and it actively encourages practitioners not to teach things, because “they should already know this stuff.”

So we should dispense with it, stop referring to it, bury it deep. Move on.

Please please please.

References:

Dourish, Paul, and Genevieve Bell. 2011. Divining a digital future: Mess and Mythology in Ubiquitous Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Images: Wikipedia

.jpg)

.jpg)