|

Listen to this post

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

I had the great pleasure of getting to speak to a roomful of library colleagues at the Innovative Library Classroom conference in Radford, VA this past week. It’s one of those nice small-room conferences that facilitates deep dives, long conversations, and chatty interactions that can inspire and lead to future work that you would never have otherwise been able to consider.

I have been presenting on the work my UNC Charlotte colleagues and I are doing in our Active Learning Classrooms in a few different contexts. This is the first time I’ve gotten to speak about what I think the implications are for libraries and librarians. Several people helped me with the content and the framing of this talk, and I will thank them at the beginning of this blogpost (rather than at the end of the talk). If I am coherent at all when I give talks it is thanks to the processing that my friends and colleagues allow me to do in their presence, in conversation, on Twitter and email and elsewhere. They are not of course culpable, any mistakes or disagreements should settle safely on my shoulders alone.

For this talk, I get to thank Dave Cormier, Rich Preville, Kurt Richter, Stephanie Otis, and Susan Harden for talking with, working with, and otherwise indulging me processing aloud in some way.

(Usual caveats about how I am far more Improv Theater than Scripted–here is my best attempt at capturing this particular talk. )

I have been asked to talk to you today about the agenda of active learning classrooms, active learning practices, and active learning places.

I am an anthropologist employed by my library to do research around academic practices, defined very broadly. I am responsible to the Dean of the Library to bring relevant information around digital and physical spaces and practices, so that our library can make better, more effective decisions about policy, spaces, collections, and agendas.

Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte. Photo Wade Bruton, UNC Charlotte: https://www.flickr.com/photos/stakeyourclaim/6254440195

It has become clear over the last several years that my work is about more than the library, it’s about academia generally, and therefore I have to be present, in my research and in my policy discussions, outside of the library. So I am collaborating with people in the US, UK, and of course at UNCC who are in centers of teaching and learning, who are in leadership positions around digital pedagogy, as well as in libraries.

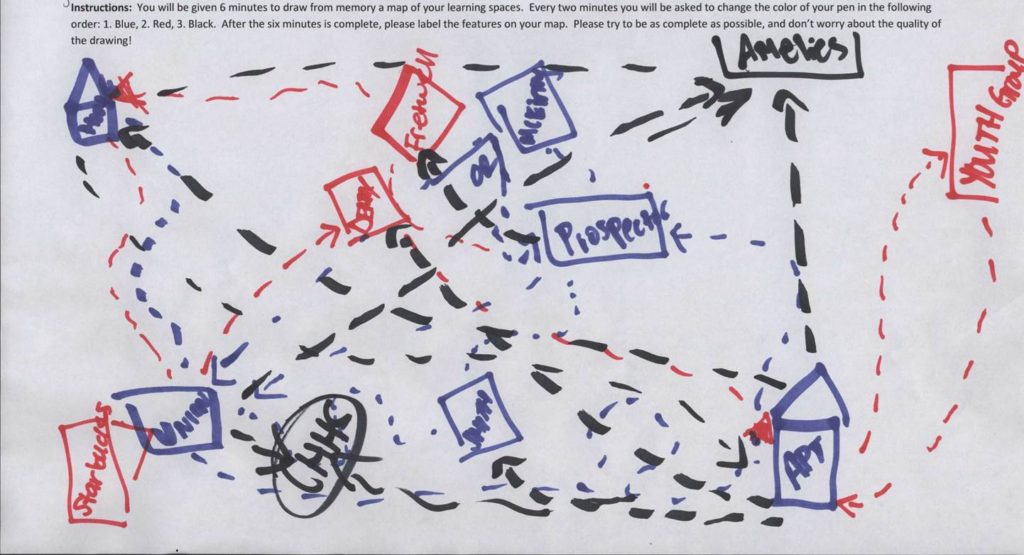

You’ve seen this cognitive map before. I love these visualizations of how wide-ranging and messy academic practice is, the nice representation of the connected network of learning spaces including but also beyond the library.

So when we talk about Active Learning, I like, as with my library work, to take a broad view. I am defining active learning for the purposes of this talk as the cluster of pedagogical approaches that center student participation in teaching and learning, and de-center the role of the instructor as Imparter of Knowledge. It tends to take place in a wide variety of environments, including purpose-built ones like we have at UNC Charlotte.

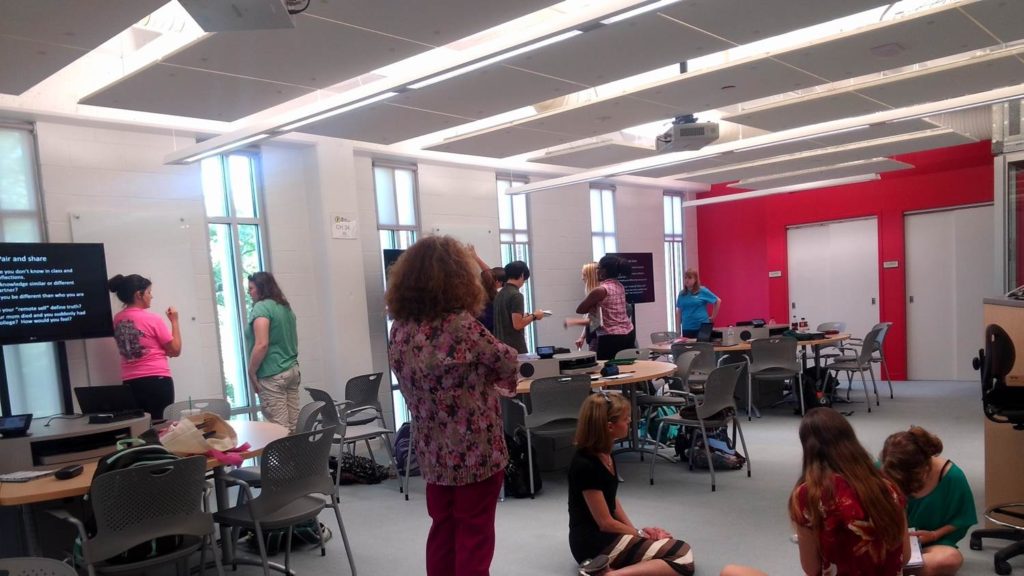

UNC Charlotte’s active learning classroom in Kennedy Hall, photo from the Center for Teaching and Learning. Dr. Coral Wayland teaches and learns from her students.

I think it’s useful to ask, when talking about Active Learning Agendas, questions like: whose agenda? Is there more than one? Where are those agendas located?

I see multiple sites for discussions around active learning, and many possible participants.

Another question I have is: are the agendas embedded in the practices of a university or school? Or are they accessories that mask the dominant presence of less innovative practice?

I think about the difference between integrated Information Literacy education vs. One-shot library instruction, and what those very different approaches can signal about how the library is situated on campus as a whole. When one-shot instruction is the only option, what does that mean with regard to the culture of teaching, and the possible library role in it, as a whole? Conversations I have with instruction librarian colleagues (and indeed, the content of much of the TILC program) indicate that no one thinks it’s a particularly marvelous way to teach people. But it persists, sometimes as the only game in town.

Likewise we know that lectures are a less effective way of teaching and learning than active pedagogies, but they are still around because…?

There are a number of reasons, but I wonder in particular , where is the time to plan and do otherwise?

How do we create organizational space? Time? Priorities? Communities for people to come together and teach as a process?

And I struggle with this a great deal in part because while I’m increasingly witnessing relatively high-level policy discussions around the intentions of our administration, faculty, and community with regard to teaching and learning, and am also getting access to grass-roots practice via fieldwork (observations and interviews mostly, and also some MA-student led work on the anthropology of collaboration among undergraduates), I don’t have a good sense of what the in-between bureaucratic procedures we need at UNCC (or elsewhere) for a sustainable, pervasive active learning agenda.

I am confident that all of the people in the room at TILC are doing as much active teaching and learning as they can, it’s part of why they were at the conference. I want to explore a bit what my experience around active learning has been at UNC Charlotte, and ask some questions about the role of libraries in the larger educational agenda of universities.

I see active learning as an opportunity for libraries and librarians to partner with teaching faculty–and so as always the question is how do you get buy-in? How can you get faculty informed, and also informing each other about those opportunities? How, in the course of engaging in active practices, can we get people to go along with de-centering content, transmission of knowledge, and focus instead on process, on connection, on learning? Here is where I turn to the work of Dave Cormier and his #rhizo experiments in online learning.

Image source David L. Van Tassel https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Helianthus_maximilianii_rhizomes.jpg

I quote shamelessly from Dave’s blog here:

“What is needed is a model of knowledge acquisition that accounts for socially constructed, negotiated knowledge. In such a model, the community is not the path to understanding or accessing the curriculum; rather, the community is the curriculum.”

“In the rhizomatic model of learning, curriculum is not driven by predefined inputs from experts; it is constructed and negotiated in real time by the contributions of those engaged in the learning process. This community acts as the curriculum, spontaneously shaping, constructing, and reconstructing itself and the subject of its learning in the same way that the rhizome responds to changing environmental conditions.”

To borrow a phrase from libraries and archives, how do we get to a point where we curate connections rather than curating content? This has always been the work of the library, but is now more than ever at the center of what we do. And we are not alone, clearly that shift is happening in the classroom as well as other teaching and learning spaces in universities.

UNC Charlotte’s active learning classroom in Kennedy Hall, before they started being used. Photo from Center for Teaching and Learning.

UNC Charlotte’s active learning classrooms are the newest teaching spaces on campus, constructed in our oldest building. We have this agenda and these spaces in part because of our Senior Associate Provost, Dr. Jay Raja, and his commitment to fund and facilitate these classrooms. The roll out of these spaces was accompanied by a programmatic attention to them in the form of the Active Learning Academy, the leadership team of which is comprised of people from the Center for Teaching and Learning, the Office of Classroom Support, and the Library. My role is assessment but also in participating in conversations about the role of teaching and pedagogy at UNC Charlotte generally.

In the fieldwork I conducted and facilitated I did observations not just of the classrooms but also of the sessions where faculty teaching in these rooms came together to talk about what they were doing around active learning, and why. We approached the Active Learning Academy as a community of practice, an opportunity for faculty to share with and learn from each other, far more than another place for faculty to be told what to do by outside experts.

I was most struck by what was anxiety-provoking. One faculty member, on walking into the space, wanted to know how to turn off the internet. We heard from another faculty member they had been warned not to teach in classrooms like these, because they would not be able to deliver the content they needed to. We had another faculty member stop teaching in the classroom after an academic year (we are now at the end of our second full year of these classrooms being open), because he could not lecture effectively in that space. There was too big a gap between what the room was encouraging him to do, and what he was still comfortable doing. He was unable to put much distance between himself and the model of authority which required that he know everything, and try to communicate it all in person to his students.

There was some anxiety around what if the tech fails? Persistent narratives, either around tech or students or content delivery, centered on lack of control. Lack of control of classroom tech, of students, of their own time as instructors to be able to pay attention to their syllabus and their pedagogy to really effectively use the potential in a room like this.

Students pushed back as well, against a notion of teaching that was unfamiliar to those used to lecture-based content delivery, of standardized testing. “I thought you were supposed to be teaching me!” is what some faculty heard.

Student are not immune from the same cliches of teaching and learning that can trap instructors.

The role of the Center for Teaching and Learning was to attempt to provide a space where faculty could start to feel comfortable engaging in teaching practices that didn’t require them to know everything. Active learning is approached as a continuum of practice, where there are lots of ways to get stuck in, and many opportunities for faculty to realize where their existing practice is already quite active, as well as discover places for them to take apart and put back together their classes.

There can also can be a huge role for the Center for Teaching and Learning (and other locations on campus) to provide ways for faculty to share strategies on framing active teaching and learning for students as “What Education Looks Like.” We are in some ways responsible for deconstructing the model of education handed to our students by the public K-12 system. Standardized-testing-centric teaching (mandated by the state) provides fewer and fewer opportunities for students to engage in the collaborative active generative (and messy) learning that the Active Learning Agenda encourages and facilitates.

The Active Learning payoffs discussed by faculty included:

“Inquiry assignments work great!”

“Spontaneous “write-think” exercises”

“Discussions are more productive.”

“I get their full attention. They are very engaged.”

“They interact with each other & build a stronger relationship/friendship.”

“I feel more connected to the students. A reward for me as the instructor.”

Who doesn’t want those things? And who notices that these are not easily measured, but are definitely observable and describable phenomena, another argument for including qualitative assessment work in institutional projects such as these.

It seems to me that libraries are super-well-positioned to take advantage of the active learning moment because IL has always had to be more about process, evaluation, sifting, and then critically using than the essential container of content. This is why we are ideally positioned, in theory, to articulate our instructional agenda coming from libraries with the larger educational mission of the university.

What is library instruction in an active-learning environment (i.e., one that de-emphasizes content) ?

It is, really, same as it ever was, but now we can explicitly link it to the kind of teaching and learning happening at our universities.

This feels like an opportunity for librarians serve as consultants, partners, and leaders on campus with faculty. So, we continue to have conversation with faculty, and about what they do.

A nice example of this is the work of my colleagues Stephanie Otis (in the library) and Joyce Dalsheim (in Global, Area, and International Studies). They are partners in a now four-year long project called Reading is Research, and co-teach. Their model is library and librarians as colleagues, not helpers–this is not “how can I help you?” but is expertise, and embedded practice. I quote from a description of a workshop they co-delivered this Spring at UNC Charlotte:

“This collaboration between anthropologist Dr. Joyce Dalsheim and Atkins’ teaching librarian Stephanie Otis has been tested and improved and is now inspiring new First Year Writing assignments and course design. It has also informed changes to the Senior Seminar approach in Global, Area, and International Studies (GAIS)…By initiating this collaboration, Joyce has advocated for research instruction that goes beyond scheduling a session in the library to involve faculty and librarians planning the syllabus, class meetings, and assignments/activities together. This approach helps establish the library as an academic and curricular partner rather than an optional service. In addition, the idea of deep collaboration and rethinking the emphasis of research can inform many other partnerships with the library.”

They delivered this workshop to attendees from across the university–for example, Anthropology, the Honors College, Biology, and Engineering.

As with the Active Learning Academy, the interest in these practices has not been limited, at UNC Charlotte, to just one corner of the university. It is a pervasive agenda from many locations. We are therefore forging an Active Learning, Community of Practice.

What does this mean for each of you, in your institutional spaces?

Of course there are questions of bandwidth–if you are a small library, how do you get time to do that? If you are doing instruction and outreach, maybe you can’t do that.

New Spaces aren’t always going to happen.

And there is an inevitable contrast between old spaces and new spaces when we do have them.

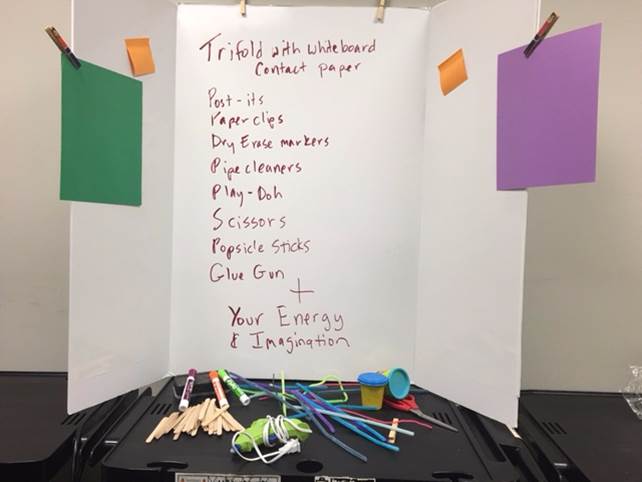

Think about faculty who get into the new spaces, how do they go back to the old classrooms? What happens when the possibilities are limited to certain spaces on campus? We need to ask questions about how people have access to these kinds of spaces. If they don’t exist on your campus, to what extent can you engage in the pedagogies anyway? My colleague Susan Harden (pictured above teaching in our smaller active classroom) has come up with a kit.

The Active Learning Agenda can mean using whatever space you have, it’s not always going to be about building shiny new spaces. And space is just a starting point, not the be-all-end-all. “Building classrooms is the least expensive part of this”–I have said this in a variety of contexts. We are lucky, at UNC Charlotte, we got to build the classrooms, but the strength of the agenda is in the human labor, the staff development, the money required to give time and opportunity for faculty and students to try, and regroup, and try again.

At UNC Charlotte this is not an agenda that is possible if it only emerges from one location. This is a cross-university partnership among our CTL, Classroom Support, the Library, Academic Affairs, and key champions in each of our Colleges.

This cannot happen on an institutional basis by practitioners engaging in isolation from each other. We are banding together with like-minded faculty but then also finding ways to disseminate these practices. I find it frustrating (I am not the only one) that we’ve got 25 years of research backing up these techniques as more effective on nearly every measure than traditional lecture, but there is still push-back and demands for proof before space is allowed. Who is interrogating the efficacy of lecture-based classes? Too often the familiar and the tidy (and the numerically significant–“butts in seats”) win out over the messy and the unfamiliar (but, more effective!) We are still coming from a defensive position, and current political climate that is fundamentally suspicious of the expertise of educators is not helping.

The UNC Charlotte Active Learning model is trying to approach the sweet spot of harnessing grass roots practices and having administration on-board with the overarching agenda. Space was created for us by high-level policy decisions, the practices existed on our campus, and we need to do the (occasionally boring) work of putting in place procedures so that this agenda can spread and thrive in a sustained way.

So I end, as I usually do, with questions rather than conclusions.

What is the role of the library? What is your position in your university now? How does that status reflect what voice is possible?

What does your agenda look like?

What are the implications? What is at stake?

One of our faculty members said to me in an interview: “now that we know how much more effective teaching and learning are in these active environments, it’s a social justice issue that we continue to do so.”

Who do you talk to? Who do you influence? How do you find the rooms where practice can start to be moved?

What are the leadership contexts in which a tolerance for risk and mess can be created and maintained?

The Active Learning Agenda can provide a space for the library to become a place that facilitates access, not just to information (never just to information), but to possibility.

How can the library, and those of us who work from within the library, be part of the team removing the obstacles to active learning? Can we curate a path to change?