https://twitter.com/DonnaLanclos/status/996379181993873409

I was invited by Kerry Pinny to be one of the keynotes at the UCISA Digital Capabilities event this past week at Warwick University. Here is my best attempt to make the talk I gave into prose form.

I think with people (I say this most times I give a talk, but it’s worth repeating and pointing out), and on the occasion of this talk, I have thought either directly or indirectly with these people in particular.

Elder Teen

Some of them via conversations online, some face to face. I want in particular to point to Lawrie Phipps, with whom I have been partnering this year in a variety of work, and whose thoughts are shot through much of my thinking here. And Kerry Pinny, who was brave enough to invite me to speak to you today. And I also want to single out my daughter, referred to here as Elder Teen.

My daughter is 17 years old. She is going to university next year. She grew up in the American school system, one where standardized testing rules. She has been tested beyond an inch of her life, labeled a variety of things, and had her notions of success tied to particular kind of tests (PSAT, SAT, ACT) and classes associated with tests (AP, IB) for a very long time.

She does very well on tests.

That is not the point.

I see time and again the experiences she has in classes reduced to “how she will do on a test.” And I witness the joy it sucks out of her educational experiences, and the terror it inspires, in the chance she might get things wrong, or not do well enough.

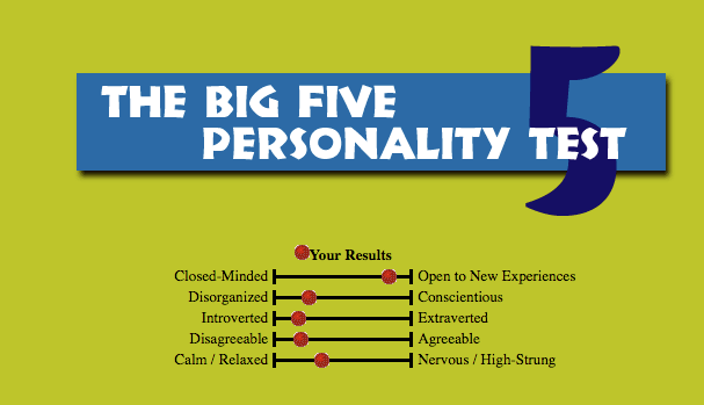

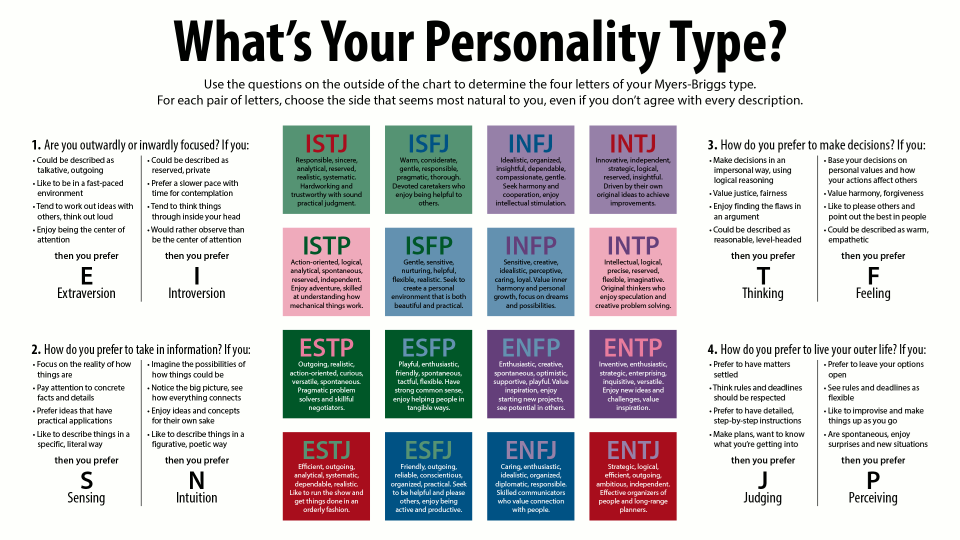

We are surrounded by tests.

They are used in the workplace, in professional development situations. For example:

and

I often wonder how different it would be, in staff development workshops, if we had people test themselves with these kinds of tools:

Or maybe this one?

My daughter helped me find the Cosmo and the Buzzfeed quizzes. She was particularly excited about this one:

and so she insisted that I take it. Here’s my result:

I have no idea what that result means. I suspect I could spin something about my personal or professional life around “Funfetti Grilled Cheese” (YUCK) if I had to.

My daughter plays with these quizzes all the time, and I asked her, given how much angst tests give her in academic contexts, why she would bother taking these kinds of tests. She told me, “Sometimes it’s fun to think about what kind of grilled cheese sandwich I would be!”

And yeah. It can be fun to play with these kinds of things.

Where it ceases to be fun is when decisions get made on your behalf based on the results.

Frameworks, quizzes, and diagnostics (what I like to call the “Cosmo Quiz” school of professional development) that encourage people to decide what “type” they are to explain why they are doing things give an easy end-run around organizational, structural, cultural circumstances that might also be the reasons for people’s behaviors. The danger with attributing actions just to individual motivations or “tendencies” is that when there are problems, then it’s entirely up to the individual to “fix it.”

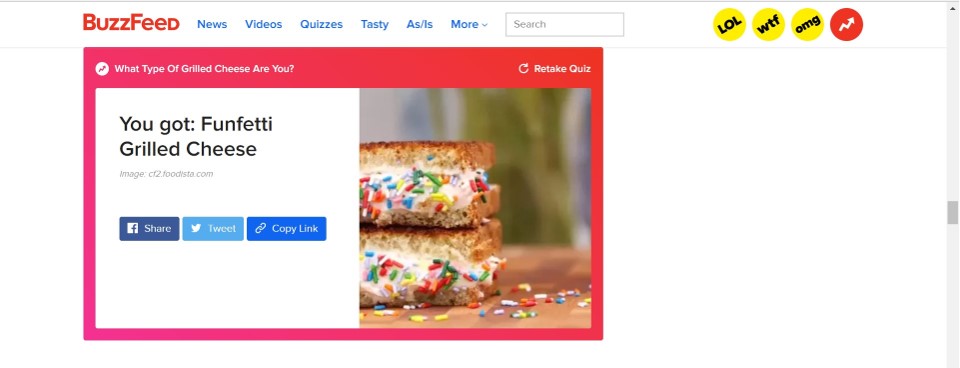

Checklists find their way into a lot of the work we do. My colleagues in libraries introduced me to this checklist, used in some instructional contexts:

I appreciate very much the critique of the CRAAP checklist approach to information literacy that Kevin Seeber offers, and share his skepticism around the idea that if you give student a list they can figure out what is good information and what is “bad.” This kind of skills approach to critical thinking isn’t effective, and is a dangerous approach in these political times when we need (“now more than ever”) to provide people with practices and processes that allow them to effectively navigate the current landscape of information and disinformation.

There are structurally similar arguments being made around academic literacies generally, including student writing–there is a concern across the sector around the risks of reducing the notion of what we need people to do during and after their time in educational institutions to “skills.”

The following list is a tiny literature review that reflects the thinking and reading I did for this part of the talk.

Lewis Elton (2010) Academic writing and tacit knowledge, Teaching in Higher Education, 15:2, 151-160, DOI: 10.1080/13562511003619979

Mary R. Lea & Brian V. Street (2006) Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach, Studies in Higher Education, 23:2, 157-172, DOI: 10.1080/03075079812331380364

Eamonn Teawell. “The Problem with Grit: Dismantling Deficit Models in Information Literacy Instruction, LOEX, May 5, 2018. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1rYott7k-_WYi_fPmgqqr36THefKJGljcBichqv4U4OY/present?includes_info_params=1&slide=id.p5

John C. Besley and Andrea H. Tanner. (2011) What Science Communication Scholars Think About Training Scientists to Communicate. Science Communication Vol 33, Issue 2, pp. 239 – 263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547010386972

Douglas, Mary. How institutions think. Syracuse University Press, 1986.

Chris Gilliard and Hugh Kulik “Digital Redlining, Access and Privacy” Privacy Blog, Common Sense Education, May 24, 2016, https://www.commonsense.org/education/privacy/blog/digital-redlining-access-privacy

Safiya Umoja Noble. Algorithms of Oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press, 2018.

Primarily this is to say that what I’ve been critiquing thus far are “deficit models”–wherein people are framed as lacking, from the beginning, and where the “fix” is “more” of something–more information, more skills, etc. And you can see from these references that such critiques predate this talk by a long shot. This isn’t even the earliest reference, but the Elton source was brought to me via the second reference, Lea and Street, who wanted educators to be “concerned with the processes of meaning-making and contestation around meaning rather than as skills or deficits. “ (Lea and Street 2006, p. 159). Their article is specifically about academic writing, but the points they make cross-cut many pedagogical discussions in higher and further education, and like Eamonn Teawell in his recent talk at LOEX, argues for a model of education that is about the social acquisition of academic practices, rather than the accumulation of skills off a checklist, or a certain amount of content.

My colleague at UCL, Jason Davies alerted me to the anthropologist Mary Douglas’ short book, based on a series of lectures, called How Institutions Work, and in particular to her points that institutions are socially and culturally constructed, and that they themselves structure knowledge and identity. Universities are institutions, shot through with the structures of society, social inequality, racism, sexism, and classism. Douglas notes that analogies and labels used in institutional contexts are representations of “patterns of authority.”

So when we, in institutional contexts, sit our students or staff down and ask them to take a test or go through a diagnostic tool that gives them a profile, we think we are just trying to make things clear. Douglas’s analysis gives us a way to frame these activities as actually reinforcing current structural inequalities, and therefore assigning categories that limit people and their potential. When institutions do the classifying, they de-emphasizes individual agency and furthermore suggests that the institutional take on identity is the important one that determines future “success” (which again, is defined institutionally).

I want to draw a line from quiz-type testing that offers people an opportunity to profile themselves and the problems inherent in reducing knowledge work to a list of skills. And I also want to draw attention to the risks to which we expose our students and staff, if we use these “profiles” to predict, limit, or otherwise determine what might be possible for them in the future.

Chris Gilliard and Safiya Noble’s works are there for me as cautions about the ways in which digital structures reproduce and amplify inequality. Technology is not neutral, and the digital tools, platforms, and places with which we engage, online or off, are made by people, and informed by our societies, and all of the biases therein.

What are the connotations of the word “profile?” If you have a “profile” that is something that suggests that people know who you are and are predicting your behavior. We “profile” criminals. We “profile” suspects. People are unjustly “profiled” at border crossings because of the color of their skin, their accent, their dress. “Profiles” are the bread and butter of what Chris Gillard has called “digital redlining:” ”a set of education policies, investment decisions, and IT practices that actively create and maintain class boundaries through strictures that discriminate against specific groups (Gilliard and Kulik 2016). “

The definitions of identity that emerge from institutions homogenize, they erase difference, they gatekeep. This is the nature of institutions. Our role as educators should be to remove barriers for our students, staff, and ourselves, not provide more of them.

Teaching and learning is not a problem to be solved. They are processes in which we engage.

So when you talk about “digital capability” you may not intend that term to imply switches that are either on and off. But the opposite of digitally capable is digitally incapable. The opposite of digital literacy is digital illiteracy. They are binary states. That’s built into the language we use, when we say these things.

Early in my time doing work in libraries, I was tasked with some web usability testing. It was clear to me in the work that people didn’t sit down to a website and say “I’m a first year, and I’m using this website” They sat down and said “i’m writing a paper, I need to find sources.” So I was perplexed at the use of personas in web UX, because in the course of my research I saw people making meaning of their encounters with the webs based on what they wanted and needed to do, first and foremost–not who they were. What I was told, when I asked, was that personas are useful to have in meetings where you need to prove that “users are people.”

When UX workers use personas to frame our testing of websites, we have capitulated to a system that is already disassociated from people, and all their human complexity. The utility of personas is a symptom of the lack of control that libraries and librarians have over the systems they use. How absurd to have to make the argument that these websites and databases will be used by people. The insidious effect of persona-based arguments is to further limit what we think people are likely to do as particular categories. Are first year students going to do research? Do undergraduates need to know about interlibrary loans? Do members of academic staff need to know how to contact a librarians? Why or why not? If we had task-based organizing structures in our websites, it wouldn’t matter who was using them. It would matter far more what they are trying to do.

What I have also found in my own more recent work, as someone brought in to various HE and FE contexts to help people reflect on and develop their personal and professional practices, is that metaphors slide easily into labels, into ways that people identify themselves in the metaphor. People have been primed by those quizzes, those diagnostics, to label themselves.

“I’m ENTJ”

“I’m 40 but my social media age is 16”

“I’m a funfetti cheese sandwich”

I’ve spent a lot of time in workshops trying to manage people’s anxieties around what they think these metaphors say about them as people. They apologize for their practice, because they can read the judgments embedded in the metaphors. No matter how hard we worked, in particular with the Visitors and Residents metaphor, to make it free from judgement, to make it clear that these are modes of engagement, not types of people, it never quite worked.

We still had people deciding that they were more or less capable depending on the label they felt fit them. “I can’t do that online conference because i’m not Resident on Twitter.”

We need to move away from deficit models of digital capabilities that start with pigeonholing people based on questionnaire results

What are we doing when we encourage people to diagnose themselves, categorize themselves with these tools? The underlying message is that they are a problem needing to be fixed, and those fixes will be determined after the results of the questionnaire are in.

The message is that who they are determines how capable they are. The message is that there might be limits on their capabilities, based on who they are.

The message is that we need to spend labor determining who people are before we offer them help. That we need to categorize people and build typologies of personas rather than making it easy for people to access the resources they need, and allow themselves to define themselves, for their identity to emerge from their practice, from their own definitions of self, rather than our imposed notions

Anthropology has many flaws and also jargon that I occasionally still find useful in thinking about academia and why we do what we do. In this case I return to the notions of emic, interpretations that emerge from within a particular cultural group, and etic, those interpretations that are imposed from the outside. What all of these “who are you, here’s what we have for you” setups do is emerge from etic categories, those imposed from the outside: You are a transfer student you are a first-gen student you are a BAME student you are a digital native.

What if we valued more the emic categories, the ways that students and staff identify themselves? What if we allowed their definition of self to emerge from the circumstances that we provide for them while at University, for the processes they engage in to be self-directed but also scaffolded with the help, resources, mentoring, guidance of the people who make up their University?

That would be education, right?

Because the other thing is sorting.

The history of Anthropology tells us that categorizing people is lesser than understanding them. Colonial practices were all about the describing and categorizing, and ultimately, controlling and exploiting. It was in service of empire, and anthropology facilitated that work.

It shouldn’t any more, and it doesn’t have to now.

You don’t need to compile a typology of students or staff. You need to engage with them.

For more discussion of this digital mapping tool, see the preprint by Lawrie Phipps and myself here.

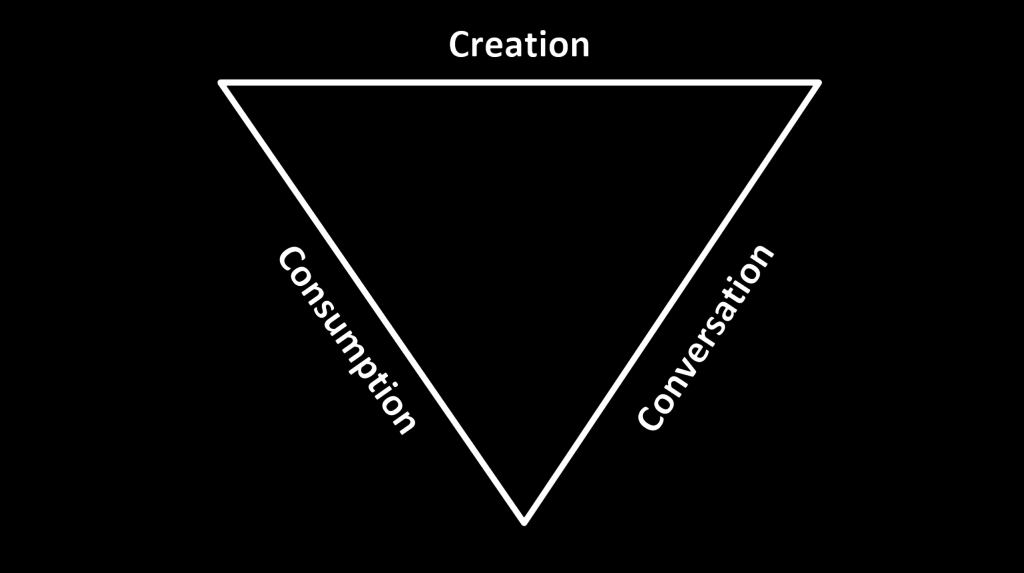

In the digital practice mapping workshops that I have been doing this year, many of them with Lawrie Phipps, we have started using this tool, which allows us to focus straight away on what people are doing, so we can then have a conversation about their motivations.

I think this might be one possible way of getting out of the classification game. When we use this tool, we have found we didn’t have to have those “who am I , am I doing it right?” conversations. People are far less concerned about labels, and rarely if ever apologetic about their practices.

We need to start with people’s practices, and recognize their practice as as effective for them in certain contexts.

And then ask them questions. Ask them what they want to do. Don’t give them categories, labels are barriers. Who they are isn’t what they can do.

Please, let’s not profile people.

When you are asking your students and staff questions, perhaps it should not be in a survey. When you are trying to figure out how to help people, why not assume that the resources you provide should be seen as available to all, not just the ones with “identifiable need?”

The reason deficit models persist is not a pedagogical one, it’s a political one.

The reason why we are trying to figure out who “really needs help” (rather than assuming we can and should help everyone) is that resources are decreasing overall. The political climate is one that is de-funding universities, state money no longer supports higher education the way it used to, and widening participation is slowing down because we are asking individual students to fund their educations rather than taking on the education of our citizens as a collective responsibility that will yield collective benefits.

These diagnostic digital capability tools are in service of facilitating that de-funding. We “target” resources when there are not enough of them. We talk about “efficiency” when we cannot speak of “effectiveness.”

We think we can do a short-cut to effectiveness by identifying which students need help, guidance, and chances to explore what they don’t know.

They all need help. They all deserve an education.